Silent Enemies: Part 2 – Voices Carry

Posted: 2 October 2025 | Dr Darin Detwiler LP.D. | No comments yet

Signals and missed opportunities push margins of error in submarines and in food safety. In Part 2 of Silent Enemies, Dr Darin Detwiler explores what it means to listen before it’s too late.

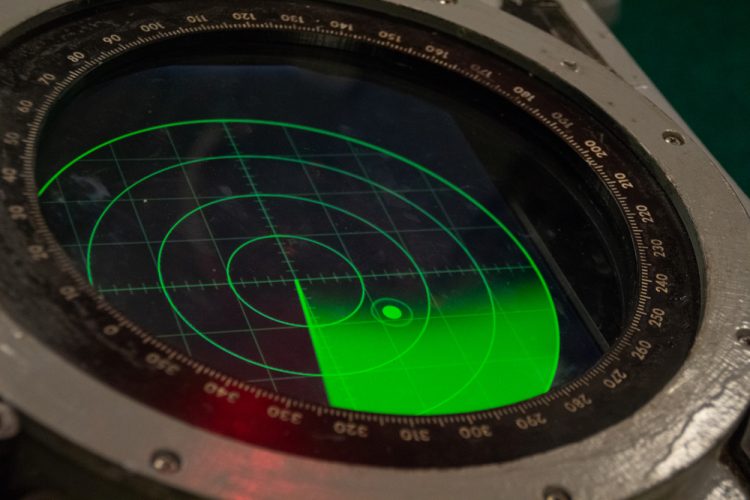

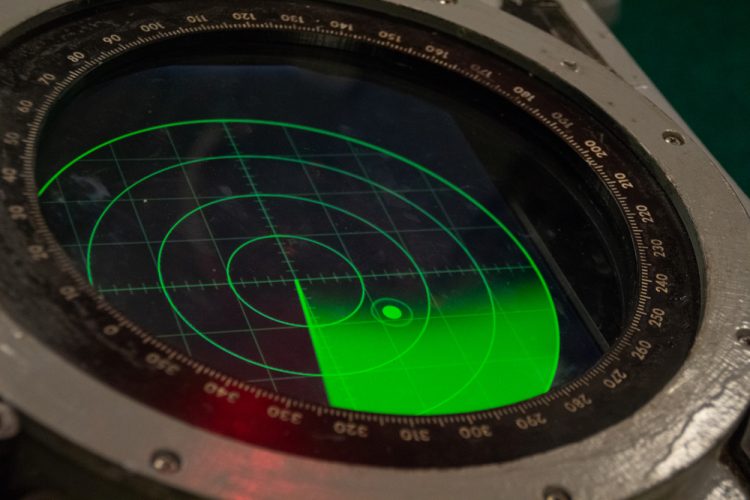

A faint signal on sonar can mean life or death. In food safety, missing that signal can carry the same human cost.

“We do not just hear noise. We listen for what should not be there.”

That was something a sonar chief once told me while onboarding as a new submarine crewmember.

Operating far below the surface, the sonar techs listened for the faintest unnatural pulse in the water: not loud, not obvious; just different.

Because not everything gives you a second signal.”

It could be a change in tone, a ping out of rhythm; a frequency too perfect to be accidental.

That kind of listening was not just technical, it was instinctual. It meant tracking something invisible and recognising its presence before evidence becomes incident. Before incident becomes crisis. True listening also means deciding whether to be proactive, or to take the limited, reactive approach.

We were all trained to find failure before it happened – to hold the line. There is always a point where intervention is possible, but it is best done early. Of course, that is when most signals are quiet and easy to miss.

We did not always know what we were hearing at first, but we were trained to respect the pulse.

Because not everything gives you a second signal.

That mindset – trained and sharpened under pressure – was hard to shake when I transitioned out of active duty, coming home to a young family and imagining the future I had helped to build.

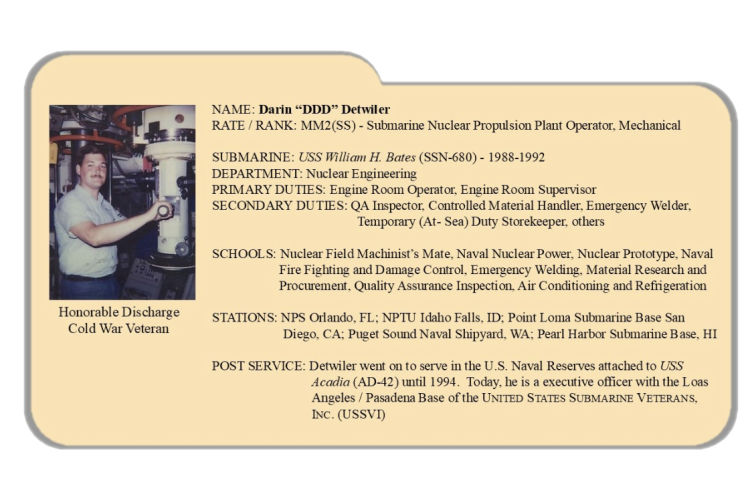

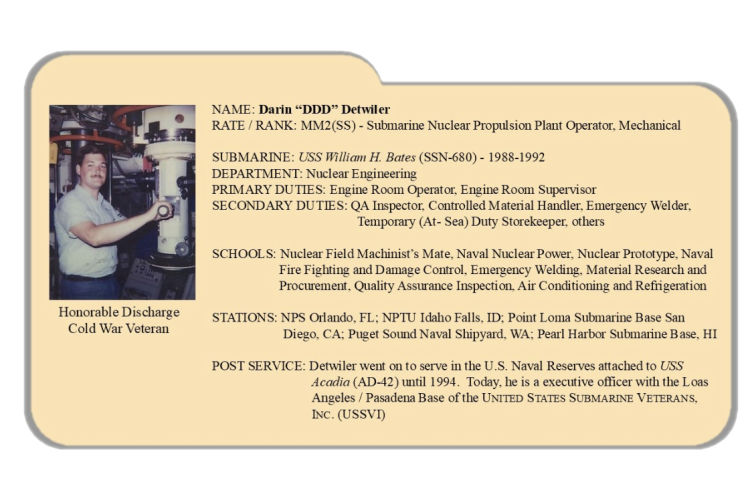

I had enlisted at 18 to serve, in part, so that my future children would not have to. To become a ‘Nuke’ – a Nuclear Machinist’s Mate (Nuclear) – aboard a submarine, I graduated from tough Navy schools, including Naval Nuclear Power School and the Naval Nuclear Training Unit in Idaho. I then reported to my submarine in San Diego and started the qualification process for my watch stations and for my submarine qualifications (Dolphins).

At 21, I earned my submarine warfare certification, bought a house, got married and became a stepfather to a six-year-old, Joshua. Two years later, my son Riley was born near the end of my enlistment. I looked forward to the years ahead with them, having all the time in the world to make up for those lost months out at sea.

I imagined a future with them: building Lego sets, watching cartoons, planning birthdays and the long arc of fatherhood.

During several meals on the sub, I had conversations with another sailor, Williams, and we shared our stories about being young dads. He boasted about his upcoming plans – a travel vacation with his wife and son. He had every detail mapped out: where they would stop, what flavour ice cream they’d get, etc.

I have come to realise that the threats to submarines and the threats to our global food system share some things cruelly simple in common…”

The way he laughed when he talked about it was warm, light, hopeful.

During those moments, we were just two guys (who happened to be on a submarine), connecting over stories of our kids, counting days until our enlistments were completed, and dreaming about everything that came after the uniform.

I did not know then how brief those conversations would be or how much weight they would carry in hindsight. What began as laughter over ice cream and future plans would soon be swallowed by a silence neither of us could have prepared for.

Perhaps we ignored the warnings that the world we were returning to held threats every bit as silent, every bit as merciless, as those beneath the surface.

I have come to realise that the threats to submarines and the threats to our global food system share some things cruelly simple in common:

These threats do not discriminate and they are often invisible until it is too late.

They do not wait for your policies to catch up. They do not respect your chain of command. They do not care that you ‘almost’ cleaned the equipment or ‘nearly’ made the call.

They move quietly. They appear suddenly.

And they kill.

In the submarine control room, I occasionally stood duty forward of engineering. My job during certain operations was to plot the path of sonar contacts on large sheets of graph paper: hand-drawn, in pencil, in real time. No automation. No software. Just my calculations, a ruler, and the steady pressure of being right in real time.

Recognise the signal. Anticipate the path. Act before it is too late.”

Every angle, every degree, every change in speed or heading mattered. A misjudged arc or a delayed course correction could result in losing track of something closing in fast.

At the time, I did not think of it as anything more than a tactical calculation: just part of the job. But today I realise that was my first real experience with what we now call ‘predictive analytics.’ I didn’t have the vocabulary for it then, but the concept was the same:

Recognise the signal. Anticipate the path. Act before it is too late.

Decades later, I would see that same principle hold life-or-death relevance in food safety. One contaminated batch could ripple across continents, and the earliest sign of trouble may not always be loud enough to catch… unless someone has trained themselves to hear it.

I saw this principle violated in a tragic case involving a four-year-old girl. She had severe symptoms: pain, bloody diarrhoea and dehydration. While her father rushed her to see a doctor, he called his brother who urged him: “Ask them to test for E. coli.”

The nurse wrote it down. “E. coli?” In the margin. In plain sight.

“The nurse’s note in the margin – that was the sonar ping.”

The doctor examined the child briefly, told the dad that “it is probably just something she ate”, and told them to “follow-up in a week if it doesn’t get better.”

The young girl was dead within 36 hours: renal failure.

Let me be clear: that father did everything right. The nurse caught the signal. But the doctor – the system – did not act to save the child.

That margin wasn’t just paper space: in this case, it was the space between life and death. The nurse’s note in the margin – that was the sonar ping. The only one she would get.

And it was missed.

New to the series?

Read Silent Enemies Part 1 – Under Pressure.

Next week:

Silent Enemies Part 3 – No Easy Way Out

Become a member and be the first to hear about the next instalment of Darin’s blog series – only on New Food.

About the author:

A professor and the author of Food Safety: Past, Present, and Predictions, Dr. Detwiler is a frequent keynote speaker at international summits, industry forums, and government panels. His insights have helped shape food safety modernization efforts and regulatory reforms in countries around the world. He appears in the Emmy Award–winning Netflix documentary Poisoned: The Dirty Truth About Your Food, which continues to fuel global dialogue on food system accountability and consumer protection. His leadership and advocacy have made him a prominent figure in both public discourse and policy development.

With a career that bridges academia, industry, and international diplomacy, Dr. Detwiler is a trusted voice working to elevate food safety as a shared global responsibility—and to inspire a new era of integrity and transparency across the world’s food systems.

Resources

This series is a collaboration with PEP Nexus, the organisation founded by author Darin Detwiler. To access a glossary and other resources that provide additional context for this series, click the Silent Enemies icon below.

Related topics

Contaminants, Food Safety, Food Security, Health & Nutrition, Pathogens, Quality analysis & quality control (QA/QC), Rapid Detection, Regulation & Legislation, The consumer