Naming and faming: how the Chocolate Scorecard is fighting slavery in cocoa supply chains

Posted: 19 September 2025 | Ruth Davison | No comments yet

Ruth Davison explores the 2025 Chocolate Scorecard, uncovering how the industry is confronting slavery, child labour and sustainability challenges in cocoa.

Cocoa beans and pod, at the heart of chocolate production, represent the systemic challenges the Chocolate Scorecard tackles — from child labour to supply chain transparency. Credit: Shutterstock

This year marked publication of the sixth annual Chocolate Scorecard – an independent assessment of the chocolate industry. It considers and scores the approach of individual businesses to issues of sustainability, including the use of child labour, forced labour, deforestation and pesticide use.

The resulting Annual Scorecard – published at Easter when our appetite for chocolate peaks – ranks companies using a traffic light system with Green for industry leaders, through Yellow and Amber for those starting to develop better practices, to Red for those with a long way to go.

Why the Chocolate Scorecard is needed

I met with Fuzz Kitto, part of the team from Be Slavery Free that co-founded the scorecard and still leads it. With Rainforest Alliance and Fairtrade already well established for certifying chocolate, my first question to Fuzz was why the Scorecard was needed.

“Certification is just the starting point,” he explains. “An audit conducted on the square root of the number of farms in a coop every three years will give you some helpful, basic information but the coverage and depth are inadequate if your goal is to meaningfully improve conditions on the ground.”

Cocoa in crisis

And the conditions on the ground for the majority of cocoa farmers is shocking. Cocoa is in crisis, with prices surging as supply falls. While consumers often experience that as smaller bars for higher prices, cocoa farmers in West Africa are bearing the brunt. In Ghana, chocolate production fell by 31 percent from 2022/23 to 2023/24 and in Cote d’Ivoire it dropped 22 percent in the same period. The devastating impact of illegal mining activity, climate change and the associated surge in pests and disease it brings about are leaving farmers destitute.

The problem is systemic, and it needs a systemic solution. Finding and rescuing individual children is not enough – we want fundamental change.”

This struggle for survival is having a particularly brutal impact on children, as witnessed by staff working for the Chocolate Scorecard when visiting farms during assessments. On one farm in Cote d’Ivoire they met Baku. The eldest of seven children, Baku left his family farm when a trafficker posing as a labour agent offered him the chance to earn enough money to support his mother and siblings following the death of his father.

Baku was trafficked illegally through Ghana to Cote d’Ivoire and had been held there as a slave for five years. He had received no pay and was scarred by the machetes and sticks he used to break open the cocoa pods. He did not even know the name of his home village or how to get back. Fortunately, with support from the NGO Solidaridad, Baku’s family was traced and he was reunited with his mother.

“The reality is that multiple children are in this situation across Western Africa,” Fuzz says. “Baku had never tasted chocolate. All he knew about the product was that his ‘blood had gone into making it’”.

The vast majority of children trapped in slave labour come from families of impoverished farmers, working either on their family farm or trafficked as Baku was. If farmers cannot make a living income, how can we eradicate slavery, never mind expect them to buy less harmful pesticides or invest into innovation that might future proof or diversify their crops?

Driving systemic change

“The problem is systemic,” Fuzz continues, “and it needs a systemic solution. Finding and rescuing individual children like Baku is what drives us, but it is not enough. At the Chocolate Scorecard, our goal is not to run an ambulance service at the bottom of a cliff. It is not even to put a fence around the edge of the cliff. We want to redirect the road away from the cliff. We want fundamental change.”

Baku had never tasted chocolate. All he knew about the product was that his ‘blood had gone into making it’.”

Key to that change, Fuzz tells me, is transparency. Still only 50 percent of chocolate is traceable and, “if you don’t know where the chocolate is coming from, you don’t know what is happening there and you can’t do anything meaningful,” says Fuzz. For this reason, the worst possible award on the scorecard is the ‘Bad Egg’ for lack of transparency – which in 2025 went to Cadbury owner, Mondelez.

“We work at every step of the chocolate supply chain,” Fuzz explains, “from growers, traders and producers to manufacturers and retailers. That means we can create pressure and momentum throughout the chain.”

But the pressure that the team wants to assert comes along with support. All data in the scorecard is anonymised with participating companies able to see their own scores in a private area of the website and compare itself to the median against each of the seven areas assessed. The team then offers individual feedback to every participating company – 95 percent of whom accept, learning how they can improve and often who can help them.

“We love it when we know companies are setting themselves KPIs to improve their ranking on the Scorecard,” says Fuzz. “Our goal is to celebrate those who are leading the way and to set – and then continually raise – the standards across the industry as a whole.”

And this positive approach is garnering results. In 2023 the first company reported finding and remediating forced labour in its supply chain. In 2024, 18 percent admitted to this and in 2025 it rose again to 22 percent.

“Acknowledging the issue is progress in itself,” says Fuzz.

But over and above transparency, action is needed. And ultimately, that comes down to us as consumers.

Fuzz talks with excitement about a tool the team partners are developing for next year that will allow consumers to obtain Scorecard information when browsing in-store confectionery aisles. By holding phone cameras across chocolate sections in shops it will recognise chocolate products and give a colour showing where they were scored on the Chocolate Scorecard. With this knowledge comes the power to demand change.

“It comes down to values,” states Fuzz, “if you are buying chocolate grown by slaves, you are supporting slavery.”

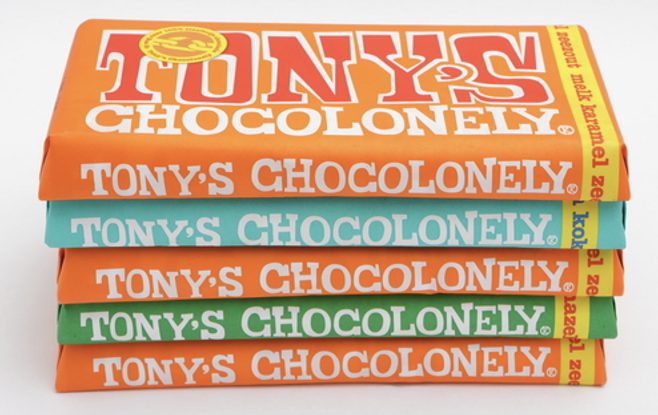

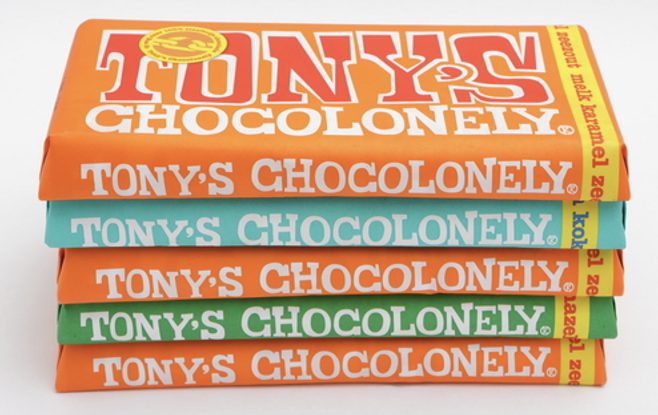

Given that the fight against slavery in chocolate is central to the mission of the Scorecard, it is fitting that Tony’s Chocolonely has ranked top every year. Founded in exasperation by a media company that was horrified by the discovery that slaves were involved in the production of almost all chocolate, the brand was created in 2006 with the specific goal of eradicating slavery in chocolate. The ‘lonely’ in the name reflects how the company felt at that time – entirely alone in caring about the issue. So ingrained was the acceptance of slavery in chocolate making back then, that they were sued by another chocolate company for claiming their product was slavery free. But Tony’s won its legal case and are now the largest and fastest growing chocolate brand in Holland. Demonstrating its transparency and traceability, Tony’s made its open-chain ‘bean to machine’ sourcing available to companies, including UK retailers Waitrose and Sainsburys. In the latest scorecard, Tony’s received the Good Egg award for excellence and transparency.

Tony’s Chocolonely, recognised for transparency and ethical sourcing in cocoa, has led the Chocolate Scorecard rankings every year. Credit: Shutterstock

But Fuzz is keen to showcase the progress of some of the major brands too. The six biggest chocolate companies produce 70 percent of the world’s chocolate, so change at scale requires their engagement, as well as ethically-led startups disrupting the market.

Mars Wrigley (which own Mars, Snickers, Maltesers and Twix, among other household names) was recognised in 2025 for its work supporting women. The company also identified the genome for cocoa and made it available on an open-source basis so that others could produce climate-resistant strains of cocoa.

Fuzz also praises Nestle for the positive impact of its Cocoa Plan on improving internal practices and for being a leader in child labour elimination.

“There is too often silence when companies who have faced a lot of lobbying make improvements,” reflects Fuzz. “We want to highlight when solid progress is being made so people can see what good looks like. We like to name and fame those who are doing well.”

To learn more about the companies that are leading the way, as well as see which are trailing behind, you can visit https://www.chocolatescorecard.com

Meet the author

Ruth Davison, Chief Storyteller at Our Carbon.

Our Carbon supports businesses in achieving product-level granularity in their carbon audits. The company helps businesses make decisions that are better for both the planet and their operations, while also sourcing stories that inspire.

Related topics

Food Security, Product Development, Regulation & Legislation, retail, Supply chain, Sustainability, The consumer, Traceability, Trade & Economy

Related organisations

Be Slavery Free, Cadbury, Fairtrade, Mars, Mars Wrigley, Mondelēz, Nestlé, Rainforest Alliance, Sainsbury's, Solidaridad, Tony’s Chocolonely, Waitrose