Silent Enemies: Part 1 – Under Pressure

Posted: 18 September 2025 | Dr Darin Detwiler LP.D. | No comments yet

In Part 1 of Silent Enemies, Dr Darin Detwiler draws on his time as a nuclear submarine officer to explore lessons of responsibility, risk and vigilance that later shaped his career in food safety.

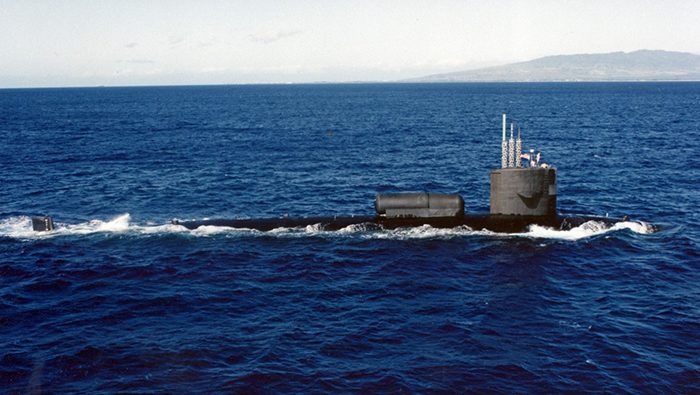

USS William H. Bates (SSN-680) in the early 1990s. This is the very submarine where Darin Detwiler first learnt to respect the silent, unforgiving pressures that would later inform his work in food safety.

A true story of silence, signals and the human cost of systemic failure.

The sound of the sea trying to kill you is eerily silent.

It catches you off guard. Cold, unfeeling, blink-of-an-eye fast, clawing at your clothes and pounding steel like a battering ram.

It doesn’t argue or ask for permission. It tells you one thing, and only one thing: You are running out of time.

Join our free webinar: Rethinking Listeria monitoring: faster, simpler solutions for food safety & environmental testing

Discover how modern Listeria monitoring solutions can support faster, more reliable food and environmental testing, and help elevate your laboratory’s efficiency and confidence in results.

Date: 18 March 2026 | Time: 15:00 GMT

During the Cold War, I operated the engine room aboard a nuclear-powered submarine when a seawater pipe broke near where the propulsion shaft exits the hull.

At hundreds of metres below the surface, pressure builds in silence…until it does not.

The seawater surged in, relentless. No hesitation. No second chances.

Facing a flooding engine room hundreds of metres below the surface, there wasn’t time to ask for approval. We assessed. We acted. We validated.”

I ran towards it, boots slamming against the deck, the salt and cold soaking through my uniform. I picked up a communication handset to sound the alarm:

My voice over the intercom was still echoing when the Commander’s order came slicing through:

“Emergency Surface!” Every second mattered. A single failure in containment below the surface and the ocean takes…it consumes everything. That idea – of systems and protocols that cannot be breached – would follow me into another, later life. At the Ballast Control Panel (BCP), the Chief of the Watch triggered the air tanks to blow seawater from between the submarine’s inner and outer hull – expelling ballast, thus making the vessel as buoyant as possible.

Meanwhile, in the engine room, another operator and I raced to stop the flooding before it could cause more damage…before it flooded the space and sank the submarine.

There wasn’t time to ask for approval. We assessed. We acted. We validated.

We shouted updates to each other as the thunderous pressure of the incoming seawater drowned out the hum of machinery and the hiss of the steam.

By the time others in the department and the senior officers arrived on the scene, the two of us had already isolated the system and stopped the flood. We then worked as a team to determine what caused the incident and how to move forwards.

Working in nuclear engineering aboard a submarine offers many opportunities for specialised duties – as well as new ways to feel a threat closing in. I also served as a Quality Assurance Inspector for our nuclear propulsion plant. That often meant spending long stretches inside the reactor compartment, checking and verifying work with no room for error. The radiation was invisible: no odour, no sound. But it soaked into your bones if you were not careful – or even if you were.

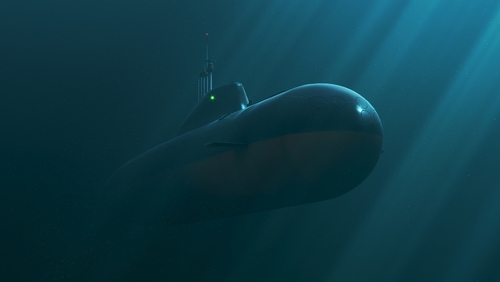

“At hundreds of metres below the surface, pressure builds in silence…until it does not.” Credit: Shutterstock

We wore three dosimeters to measure our exposure. One gave real-time readings we could read ourselves; the second required a machine and a specialist. A third device was reserved for extreme exposures – readable only after something had gone terribly wrong. Preferably never being used.

I spent so much time in the reactor compartment that my exposure limits were extended “for the needs of the Navy.”

The line between safety and exposure was invisible but never abstract. We were not just monitoring equipment; we were defending the boundary between order and catastrophe.”

The line between safety and exposure was invisible but never abstract. We were not just monitoring equipment; we were defending the boundary between order and catastrophe. We had to believe in our containment.

In those hours…minutes…seconds – inside that metal womb of danger – I learnt to respect the threats you couldn’t see. I also learnt new ways in which one’s perception changes. Minutes stretch, thoughts linger, and so does fear, if you let it.

And just as I managed to master that fear, I learnt a different lesson: how leadership doesn’t mean waiting for certainty. It means knowing when hesitation could cost lives. Life on the boat was a loop: reactor checks, silent running, fire drills, sleep. And again. And again. But in the cracks between chaos, there was food.

Not comfort food or meals you’d brag about; just survival.

Early in the patrol we would have fresh salads, real eggs, small boxes of cereal with those familiar logos and mascots; even frozen tubs of the best flavours of ice cream for dessert. But that did not last forever. Soon, our meals consisted of tinned meat, dehydrated potatoes, canned vegetables and powdered soft serve mixes. The galley always smelled like grease, metal and soap. But when the night cook made fresh bread, the scent would float down the corridors like a postcard from home, reminding us that someone, somewhere, might be thinking of us.

Leadership doesn’t mean waiting for certainty. It means knowing when hesitation could cost lives.”

But even that food – canned, shelf-stable, sometimes heavily processed – always had to meet one rule:

It had to be safe.

Because at hundreds of metres beneath the surface, there is no hospital. One contaminated meal and an entire crew could be compromised.

When we fail to stop a threat – whether it is a pipe, radiation, or a foodborne pathogen – it does not just affect a system; it spreads, it multiplies. And it reaches people who never saw it coming.

And that kind of risk – unforgiving and invisible – required more than protocols.

Responsibility didn’t stop when your shift ended. It wasn’t a title. It was a posture; a state of being.

On submarines, there is no ‘off-duty’ mindset – not really. With a small crew sealed inside a self-contained world, responsibility is something you breathe in like the recycled air around you. If something breaks, you fix it. If someone is in danger, you act. You do not say, “That’s not my job,” because there’s no one else coming. There is no delegation when you’re hundreds of metres deep.

Admiral Hyman G Rickover, ‘father of the nuclear navy’, put it this way:

“Responsibility is a unique concept… You may share it with others, but your portion is not diminished. You may delegate it, but it is still with you… If responsibility is rightfully yours, no evasion, or ignorance, or passing the blame can shift the burden to someone else.”

That quote was not just posted on a wall or tucked in a manual; it was wired into how we operated. It meant that responsibility didn’t begin and end with your watch. It was not suspended while you slept. It followed you through every corridor and decision, whether you were in the engine room, the galley or the reactor space.

Years later, when I stepped into the world of food safety, I recognised that same demand for vigilance; that same refusal to look away. Because when lives are at stake – whether at sea or across a supply chain – you cannot wait to be told what to do. You have to know; you have to move.

The ocean does not care about our job titles. Neither do pathogens. Nor allergens.”

That understanding of risk – unseen, unrelenting – would surface again years later, in a place just as tightly regulated and just as vulnerable: the food industry.

A food manufacturing compliance inspector who had just returned from a site visit, told me the kind of story that doesn’t make headlines but should be carved into training manuals.

During a routine inspection, he noticed damage near the base of a large freezer unit. There were gouges in the walls several inches above the floor – easy to miss; easy to ignore.

Flagging it in his initial report, he returned the next day to complete his visit. To his surprise, the head of the engineering and maintenance department had heard about the observation, viewed it himself and stepped forward to meet with the inspector. Not with excuses, but with answers. He explained that forklifts were slipping on icy freezer floors and colliding with the walls. The CEO responded swiftly, ordering the best-rated non-slip tyres on the market – no cost spared.

However, days later, the head of engineering came back with a surprising recommendation:

“Do not buy the highest rated ones – go with tyres from another company.”

The CEO was stunned. They had already been approved. The issue was serious. The cost was immaterial.

But the engineer had dug deeper…beyond his official duties. He discovered that the material used in the top-rated non-slip tyres contained ground walnut shells.

Being a certified nut-allergen-free facility, those tyres would have violated that certification, putting lives at risk. And in a world where allergen-free certification (whether under BRCGS or IFS) can dictate export access, that single material choice could have undone months of compliance.

It was not his job to oversee allergen controls.

It was not his job to question the decision once the CEO had signed off.

But he did it anyway.

That understanding of risk—unseen, unrelenting—would surface again years later, in a place just as tightly regulated and just as vulnerable: the food industry.

Because that is what real responsibility looks like: Stepping forwards when it would be easier to stay quiet; owning risk even when it is not in your job description; preventing disaster before the system even sees it coming.

It reminds me of standing in that flooding engine room compartment, doing what had to be done without waiting for a superior’s directive.

The ocean does not care about our job titles. Neither do pathogens. Nor allergens.

For leaders, Admiral Rickover’s message is simple: you can never outsource responsibility; you must own it.

This understanding is something I brought with me when I surfaced.

Responsibility at all times – by all stakeholders – is paramount. Just like a failure in radiation protocols, a single lapse in food handling isn’t obvious…until it is fatal.

Next week:

Silent Enemies Part 2 – Voices Carry

Become a member and be the first to hear about the next instalment of Darin’s blog series – only on New Food.

About the author:

A professor and the author of Food Safety: Past, Present, and Predictions, Dr. Detwiler is a frequent keynote speaker at international summits, industry forums, and government panels. His insights have helped shape food safety modernization efforts and regulatory reforms in countries around the world. He appears in the Emmy Award–winning Netflix documentary Poisoned: The Dirty Truth About Your Food, which continues to fuel global dialogue on food system accountability and consumer protection. His leadership and advocacy have made him a prominent figure in both public discourse and policy development.

With a career that bridges academia, industry, and international diplomacy, Dr. Detwiler is a trusted voice working to elevate food safety as a shared global responsibility—and to inspire a new era of integrity and transparency across the world’s food systems.

Resources

This series is a collaboration with PEP Nexus, the organisation founded by author Darin Detwiler. To access a glossary and other resources that provide additional context for this series, click the Silent Enemies icon below.