Flawed by design: why finished product testing has its limits

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Posted: 8 January 2021 | François Bourdichon | 1 comment

François Bourdichon explains the limits of finished product testing when it comes to ensuring safe production and how we could enhance the current methods set out.

While it is gladly accepted that a proactive approach is preferable to a reactive one, it is rarely duly implemented. A false sense of security does not help either.

Finished product testing is certainly the most commonly recognised scheme to ensure the conformity of the production, but it is flawed by design; particularly when the tested product is made from a heterogenous non-uniform process. This is valid for most, if not all, food safety and hygiene parameters (microbiological and chemical).

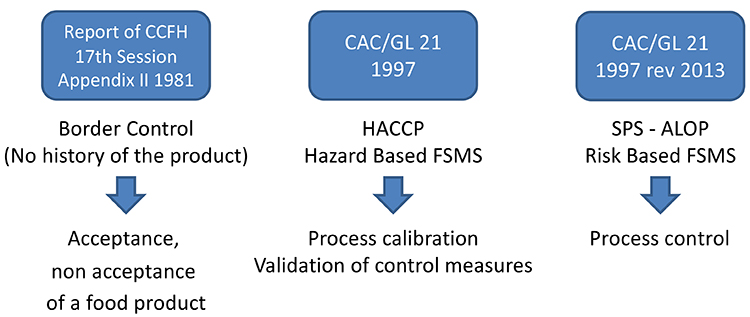

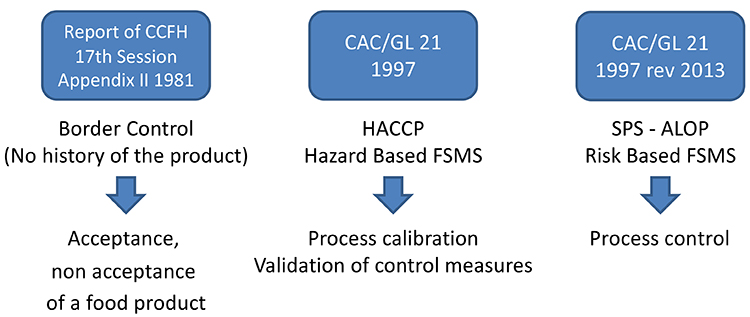

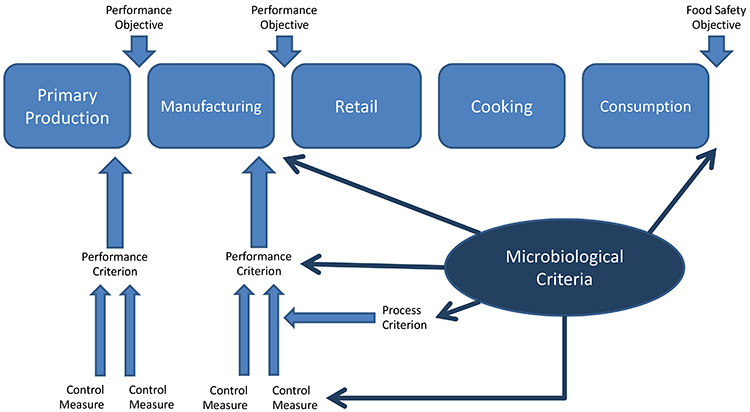

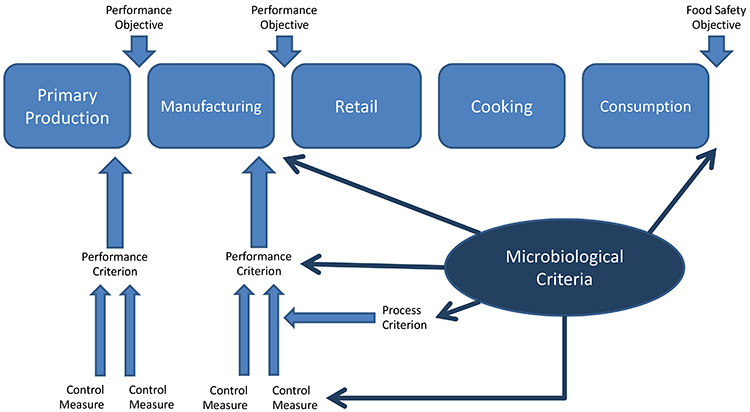

Microbiological criteria have been defined several times by the Codex Alimentarius in 1981, 1997 and lastly 2013. A conceptualised Microbial Risk Management approach has proposed numerous other metrics, from the Acceptable Level of Protection (ALOP) to Food Safety Objectives (FSO) as detailed in Figure 1, yet microbiological criteria for finished product still prevails.

Recent foodborne outbreaks in Europe for Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella spp., Campylobacter spp., and Escherichia coli STEC have shown the limits of relying solely on finished product testing.

While it is gladly accepted that a proactive approach is preferable to a reactive one, it is rarely duly implemented. A false sense of security does not help either.

Finished product testing is certainly the most commonly recognised scheme to ensure the conformity of the production, but it is flawed by design; particularly when the tested product is made from a heterogenous non-uniform process. This is valid for most, if not all, food safety and hygiene parameters (microbiological and chemical).

Microbiological criteria have been defined several times by the Codex Alimentarius in 1981, 1997 and lastly 2013. A conceptualised Microbial Risk Management approach has proposed numerous other metrics, from the Acceptable Level of Protection (ALOP) to Food Safety Objectives (FSO) as detailed in Figure 1, yet microbiological criteria for finished product still prevails.

Recent foodborne outbreaks in Europe for Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella spp., Campylobacter spp., and Escherichia coli STEC have shown the limits of relying solely on finished product testing.

A conceptualised Microbial Risk Management approach has proposed numerous other metrics, from the ALOP to FSO

Take the two recent infant formulation outbreaks linked to Salmonella spp. contamination as an example of the restrictive parameters of finished product testing when tackling low-level contamination. First, the Salmonella Agona milk powder recall (2017, France), and second, the Salmonella Poona rice-based formulation recall (2019, Spain). Both processing sites had good records of finished product testing, but the evidence following the investigation showed that their processing environment had been contaminated for over a decade.

2073/2005 is not enough: 178/2002 prevails

Testing against microbiological criteria is defined in article 4 of the EU2073/2005 regulation: “Food business operators shall perform testing as appropriate against the microbiological criteria when they are validating or verifying the correct functioning of their procedures based on Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) principles and good hygiene practice.”1 The criteria applies to the monitoring of good hygiene practices (GHP) and HACCP principles and should be put in place and validated before additional testing is considered.

This is expected in the EU178/2002 regulation where the responsibility of the food business operators to ensure the safety of its food is reinforced.2 As such, the considering #26 re‑examines the limits of establishing criterion: “The microbiological criteria set in this regulation should be open to review and revised or supplemented, if appropriate, in order to take into account developments in the field of food safety and food microbiology.”

Attention should be given to a variety of points along the food process, rather than just at the end.

Distribution of the analyte and consequences for sampling

This problem has been known for a while, yet it still persists. In a 1986 publication on ‘Management of Salmonella risks in the production of powdered milk products’, Habraken, et al begins with a statement on the limits of finished product testing, and mentions a number of references, including one that dates back to 1931: “The lack of reliability of the mere examination of finished products when evaluating the microbiological wholesomeness of food products has been known to microbiologists for a long time”3 The ILSI Europe task force on Microbiological Food Safety edited a special issue on the impact of microbial distributions in a food product on the food safety management decision process.4 Finished product testing does not provide a dichotomic vision fail/safe, but a certain probability of detecting a certain level of non‑compliance, as defined almost 20 years ago by the Codex Sampling Guidelines.5,6

Who defines the reinforced testing scheme?

When things go wrong or are not fully under control, it is expected that you switch from a routine testing scheme to a reinforced testing scheme. Until recently, this was not defined and was mostly a negotiation with authorities. Following the 2017 Salmonella outbreak in infant formulation, a reinforced control plan was defined by the French food safety authority using the data from the 1986 Habraken study.7

Non-compliant finished product revealed by testing

A food production batch that is non-compliant against food safety criteria shall be destroyed and removed from the food chain as defined by the EU2073/2005 regulation. Caution should also be taken on the previous produced batches, and production should be stopped while root cause analysis is performed to identify what led to contamination. In practice, this means huge financial loss when things go wrong with a very low, if any, margin to operate in.

To avoid closure, operators should gather all the evidence they can which demonstrates the product has been manufacturing safely, including cleaning records, control measures monitoring and maintenance records. One does not trust the safety of 80 tons of powder based on 30 samples of 25 grams. Pasteurisation should be duly recorded and properly validated, processed air HEPA filtered, and processing lines cleaned and logged, then the finished product testing comes on top of all these actions to confirm – with a limited level of confidence – the safe food production. As proposed in Figure 2, the attention should be put in many points along the food process, not only at the very end of it.

Conclusion

A lot of effort and investment has been carried out to put in place all these practices, but it is not enough. Sole focus on the finished product testing must be reassessed; this is only part of the evidence and alone is not fit-for-purpose. We require a change of mindset and a renewed approach for the assessment of compliant/non-compliant production. We must make the most of what we have – data is key – and only by doing this can we ensure safe food production.

Digitalisation of the food industry is one of the major and emerging advances we’ll see in the coming years, but really, we should already be assessing all the data generating processes for their relevance, reliability and proper design. Perhaps data assessment is deemed a complex and relentless task, but it is necessary. Yes, an algorithm will always provide an answer, but it still needs careful human consideration, the capacity to understand the results, and the ability to take a step back.

References

- COMMISSION REGULATION (EC) No 2073/2005 of 15 November 2005 on microbiological criteria for foodstuffs and following modifications. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2005/2073/2020-03-08

- COMMISSION REGULATION (EC) No 178/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 January 2002 laying down the general principles and requirements of food law, establishing the European Food Safety Authority and laying down procedures in matters of food safety. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:02002R0178-20190726

- Habraken, C.J.M., Mossel, D.A.A., Van Den Reek, S., 1986. Management of Salmonella risks in the production of powdered milk products. Netherlands Milk Dairy Journal, 40 99-116

- Bassett, J., 2010. Impact of Microbial Distributions on Food Safety ILSI Europe Report Series. 2010:1-64

- Codex Alimentarius Commission, 2004. General Guidelines on Sampling. CAC/GL 50-2004

- Codex Alimentarius Commission, 2013. Principles and guidelines for the establishment and application of microbiological criteria related to foods. CAC GL 21 1997 Modified 2013

- ANSES, 2018. Note d’appui scientifique et technique de l’Agence nationale de sécurité sanitaire de l’alimentation, de l’environnement et du travail relatif au projet de plan d’échantillonnage élaboré par Lactalis pour accompagner la reprise de la production de poudres de lait sur le site de Craon. Appui scientifique et technique de l’Anses Demande n° « 2018-SA-0077 »

About the author

François Bourdichon is a food safety, microbiology and hygiene consultant for the food industry, with a focus on dairy, infant nutrition and confectionery. With over 20 years of experience, he specialises in risk analysis, food safety and hygiene, food microbiology, fermentation and bio-preservation.

Issue

Related topics

Contaminants, Food Safety, Health & Nutrition, Lab techniques, Outbreaks & product recalls, Pathogens, Product Development, recalls, Regulation & Legislation, retail, Supply chain

Whilst I agree with the general argument of this paper I think it is way behind the times. End product testing ceased to be the only criterion for food safety many years ago. All the ideas put forward in the paper have been adopted by serious food safety specialists and passed on to their clients.

End product serves only to verify the whole production process, not to determine the safety of the product. It is therefore neither a control measure nor a monitoring step. HACCP, including risk assessment, is essential for identifying the routes of contamination and the methods of control. Until we all look at all the hazards (“microbiological” is not enough) we will not return to safe food for everyone.