Operation OPSON: the world’s annual stress-test for food crime is sending a louder alarm than ever

Posted: 15 October 2025 | Professor Chris Elliott | No comments yet

The results of last year’s food criminality are in. Here, Professor Chris Elliott shares his biggest concerns about the trends he’s noticed, including the increase in organisation and direct threat to public health.

Credit: Europol

Operation OPSON, the joint Europol–INTERPOL crackdown on counterfeit and substandard food and drink, has since its inception in 2011 become the industry’s annual stress-test. This year’s results (OPSON XIV) have been the starkest to date, with goods worth around €95 million seized, including 11,566 tonnes of food and 1.4 million litres of beverages. More than 600 individuals were reported to various judicial authorities and 101 arrest warrants were issued. Another sobering statistic is that 13 different organised crime groups were disrupted following more than 31,000 inspections across 31 countries.

The world of organised crime isn’t just trafficking drugs and people – these gangs are trafficking food.”

These staggering statistics offer a rather frightening look into the state of our global food supply system; and in my opinion they represent just a snapshot of the degree of criminality that’s operating around us. When I look at the OPSON results, two trends jump out at me. First, the growing industrialisation of food crime is accelerating. When I undertook the Elliott Review back in Horsemeat scandal times, I warned of the growing menace of organised crime in the food system. I was not wrong. Criminals are getting more coordinated and strategic; they are learning how to scale and to exploit regulatory weaknesses and asymmetries. The world of organised crime isn’t just trafficking drugs and people – these gangs are trafficking food.

The second and possibly even more troubling trend I see is authorities uncovering a much greater amount of diverted product. These are products whose shelf life has expired but are being illicitly channelled back into legitimate supply chains. Criminal gangs do this by removing expiry dates using chemical solvents then printing new, fake sell-by dates to place on the food packaging materials. This shows the growing degree of sophistication being implemented by criminal networks I find this particularly concerning since such fraud goes beyond cheating businesses and consumers; it signals serious public health threats due to the potential consumption of unsafe food.

When OPSON began in 2011, seizures were estimated to be around €30 million in value. Now in 2025, that figure has more than tripled. It would be wrong to say that food crime has increased threefold over 15 years. The investigative net has spread from a European-centric scrutiny of food on sale to a more global one. Also, investigators are better informed and networked to go after the criminal gangs. But clearly the curve isn’t flattening and the scale of the problem seems to be on the rise, most likely due to the multiple stressors on the food system that I have written about previously.

The global cost of food fraud is extremely difficult to calculate, as are other forms of fraud. The World Trade Organization (WTO) published an excellent report called “Illicit Trade in Food and Food Fraud” in 2024. Its conclusion was that the annual cost of food crime ranges between $30 billion and $50 billion. I took a slightly different tack to do my own ‘back of the envelope’ calculations based on the scale and extreme complexities of global food production, finding that in many countries, particularly in the Global South, there is close to zero inspection capacity. I am therefore of the opinion that the reported detection rates of food crime are likely minuscule in comparison to what’s really going on.

It’s not often I write such things but in this case I sincerely hope I am wrong about the scale of the global problem.”

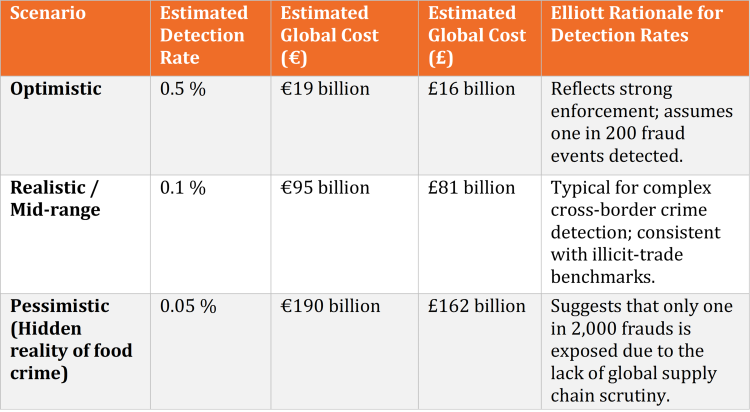

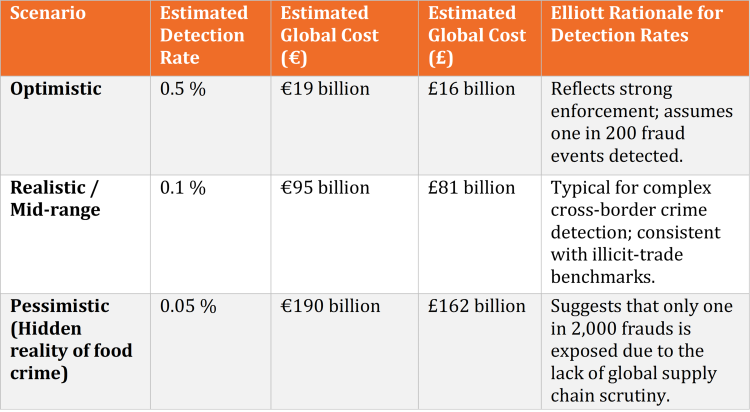

I’ve compiled a table based on what I think is actually happening, based on what I have learnt and observed from my too-many decades of investigating the dark subject of food crime.

Given this, I believe a more realistic number sits at more than double the WTO estimates and potentially quadruple. The latter figure I call the ‘hidden reality of food crime’. It’s not often I write such things but in this case I sincerely hope I am wrong about the scale of the global problem.

Professor Chris Elliott’s estimated global costs of food crime under different detection scenarios.

In terms of what the investigators actually uncover each year, three categories continually recur: alcoholic beverages (especially spirits and wine), edible oils (especially olive oil) and high-margin packaged foods and supplements. The question in my mind is: are these the products most exposed to criminal activity or are they simply most likely to be targeted in follow–ups since they were found in previous OPSON investigations? The truth probably lies somewhere in the middle. But again, from my experience, wherever and in whatever type of food category we look, we find fraud.

So this brings me to a point I have made many times before. Investigations can only be launched if there is good information, ie, actionable intelligence, to launch investigations. The vast majority of this information resides within the food and beverage industries themselves. Not criminals, but those who witness suspicious activities but are too scared to call it out. So yet another plea, if you do have any suspicions/information about possible food crime occurrences, notify the regulatory authorities. They operate highly confidential hotlines and treat all tipoffs as important.

My prediction for OPSON 2026? More investigations, more seizures and greater values. And for these to be proven true doesn’t take a crystal ball.

Related topics

Food Fraud, Food Safety, Food Security, Hygiene, Quality analysis & quality control (QA/QC), Regulation & Legislation, retail, Sanitation, Shelf life, Supply chain, Traceability, Trade & Economy, World Food