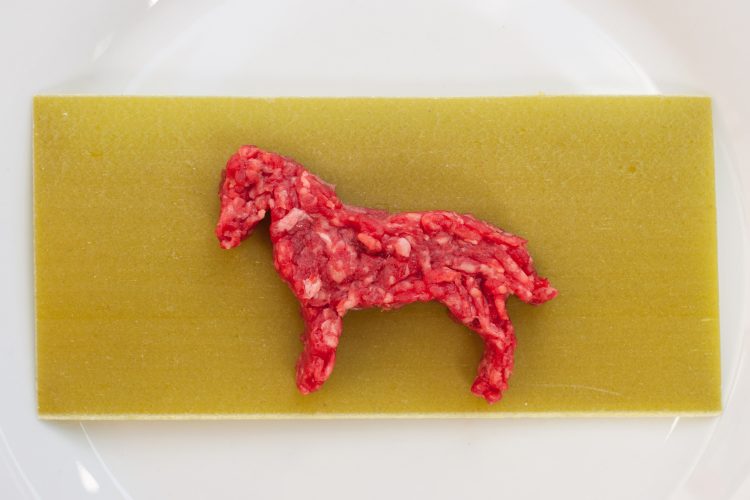

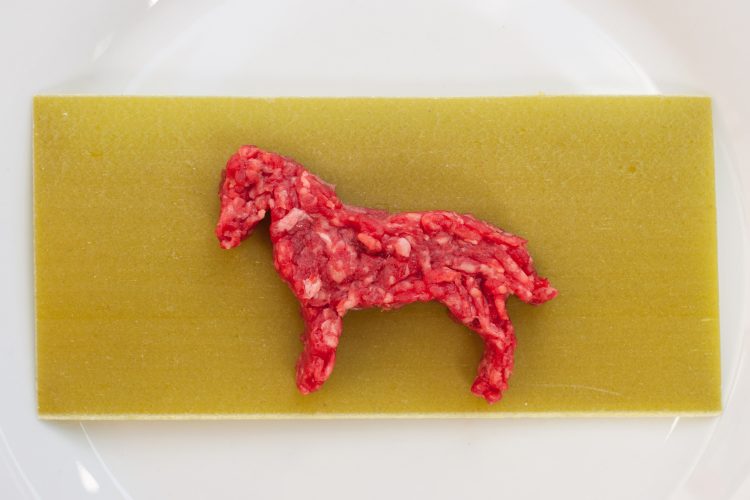

From the horse’s mouth: three steps forward and one leap back

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Posted: 17 January 2023 | Professor Chris Elliott | No comments yet

Professor Chris Elliott marks ten years since the infamous Horsemeat Scandal and assesses how resilient we are to fraud now.

This year marks 10 years since the infamous Horsemeat Scandal of 2013 – an event that exploded from a report in the TV news about something dodgy found in Tesco beef burgers, to a crisis that engulfed the food industry, regulators and general public in 16 different European countries.

What went wrong and why has been well documented in my independent analysis of the integrity of the UK food supply system, which became known as the ‘Elliott Review’. My intention was not to perpetuate the blame game (other than directed at the criminals) but rather to develop a systems-based approach that would make it far more difficult for fraudsters to penetrate our national food system.

What happened afterwards?

Even though the government accepted my recommendations in full, I was warned that ‘good reports’ often collect dust and not to expect much action as the scandal had passed and other priorities would take over as memories of Horsegate dwindled.

Thankfully the reverse was true. There was a clear appetite to enact the three major recommendations I had made. Firstly, the formation of the Food Industry Intelligence Network (FIIN), a not-for-profit organisation that brought together a number of the large food businesses to share intelligence on food authenticity testing. The organisation is still thriving with more than 50 member companies working together to protect each other and their customers from fraud.

Will we get lucky and avoid another food fraud crisis?

Secondly, the formation of the National Food Crime Unit and the Scottish Food Crime and Incidents Unit, which was the most controversial of all my recommendations. They have moved from solely gathering intelligence to investigating serious food fraud activities across the UK. Yet the agencies have been frustrated by not being granted the powers they need (and which I recommended) such as applying for search warrants, seizing evidence and interviewing suspects who are under arrest. The Food Standards Agency (FSA) launched a consultation on this matter in 2022 and hopefully this year (and the sooner the better) the UK Government will allow this to happen. Such measures will add sharper teeth to organisations tackling organised crime.

The third very positive outcome of my report was the establishment of the Food Authenticity Network (FAN). This has provided a unique online platform for the sharing of huge amounts of information and training for those who test for and audit food authenticity. With a membership now in the thousands it has become a resource for many around the globe.

As easy as A, B, C?

When asked, as I have been many times, whether things are better, worse or the same since Horsegate, I have always been positive. The response from industry and government to defend the nation against fraudsters and indeed organised crime in the food sector has been enormously beneficial and makes life far more difficult for criminals. I, like others, knew there would always be challenges and that while important deterrents had been put in place, ‘the bad guys wouldn’t stop trying’. But in the past few years my opinion has changed and not for the better. My ABC of major issues that have brought about this change in opinion are as follows:

A is for austerity and the cost-of-living crisis that is impacting so many in our society. Hunting for bargains makes people vulnerable to fraud and there are some who are more than happy to take advantage of this difficult situation.

B is for Brexit and, more specifically, the UK’s exit from the EU’s Food Fraud Network, a high-level system of exchanging information and intelligence on food fraud across member states. Ironically, the UK also lost its first line of border control on food fraud. Huge amounts of the food we consume enter Europe via ports such as Rotterdam. While once food destined for the UK was subject to the same level of inspection and scrutiny as elsewhere in Europe, our imports now receive the same attention as a consignment of unsafe meat heading for remote corners of the world, ie, none at all.

C stands for complacency. We all know that C follows B and in my major risks complacency has followed Brexit in an alarming way. The complacency resides fairly and squarely with the UK Government. When Jacob Rees-Mogg announced in April last year that all checks on food imported from the EU were to be scrapped due to the costs involved I was both astounded and aghast. He was, in effect, leaving our national borders wide open to those fraudsters that he and his Brexit compatriots have told us we were taking back control of – this must surely be one of the great Brexit ironies. What did they expect was going to happen other than fraudsters rubbing their hands together and filling their boots?

My deep concerns about this are shared by many that I speak to in industry, government and consumer organisations. Heaven knows what might happen now. Will we get lucky and avoid another food fraud crisis? Will we get very lucky and avoid significant illness or even deaths if a crisis does emerge? If something bad (and I mean really bad) does happen, I have no doubt the game of pointing fingers as to who is responsible will all start again.

Related topics

Food Fraud, Food Safety, Food Security, Regulation & Legislation, Supermarket, Supply chain

Related organisations

Food Authenticity Network (FAN), Food Industry Intelligence Network (FIIN), Food Standards Agency (FSA), National Food Crime Unit, Scottish Food Crime and Incidents Unit, UK Government