Food price inflation: How did we get here and what can be done?

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Posted: 12 August 2022 | Richard Volpe | No comments yet

As nearly everyone is aware, food price inflation has reached levels we haven’t seen in recent history. Here, Richard Volpe reflects on some of the major causes as well as lesser-known impacts that have created this perfect storm.

In the United States, grocery prices are commonly measured using the Food at Home Consumer Price Index (CPI). This CPI has increased by an average of 2.1 percent each year since 2000, but it rose by 11.9 percent from May 2021 to May 2022. Increasing by an average of 1.3 percent each month during the first five months of 2022, this is the highest five-month average increase since April-August of 1973.

Much has already been written about the causes of the ongoing food price inflation. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated it globally through a combination of heightened food loss, higher labour and transportation costs, economic uncertainty, and a host of other factors. The ongoing war in Ukraine has also contributed, driving up prices for wheat, cereals, bakery products and oils throughout the world. But a series of structural issues, several of them interrelated, were already affecting the food supply chain before COVID-19. Collectively, they help explain why inflation has been stubbornly high since the back half of 2021, and they also provide a blueprint of ideas for creating a safe, sustainable and efficient food supply chain for generations to come.

Oil prices

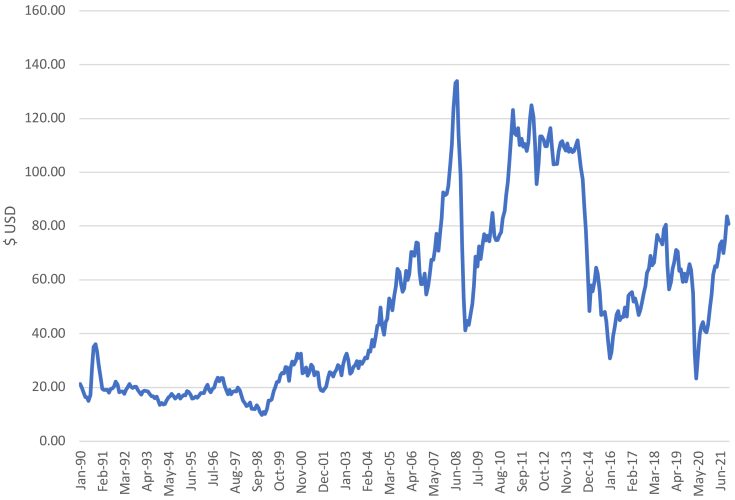

Energy is vital to every stage of the food supply chain, from farm production to the household. Around the turn of the century, the trajectory of global crude oil prices changed fundamentally, and in a way that is problematic for agribusiness. The average price per barrel of oil between 1990 and 2000 was $19.21, but between 2001 and 2021 that increased to $65.57. Energy prices have also become much more volatile, creating uncertainty for one of the most important costs faced by food companies.

Global crude oil prices, 1990-2021. Source: FRED

Transportation connects each of the segments of the food supply chain to one another, and the system has become increasingly challenging in recent years. Globally, port traffic has increased by 238 percent since 2000, reflecting the growing importance of trade for the supply of food.

Around the world, ports have been heavily congested for months, with transportation times up significantly, and loading and unloading wait times stretching for days and even weeks in many places.

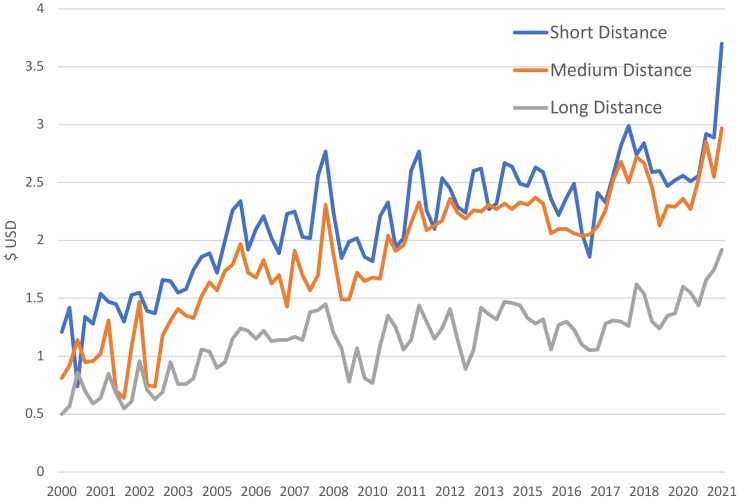

Truck transportation, particularly refrigerated capacity, has become very problematic as well. The US faces acute driver shortages which has contributed to higher transportation costs and supply chain uncertainty. Refrigerated truck shortages in the US are trending upward and have risen by 55 percent since early 2019. Longer term, truck rates have increased considerably, mirroring the increase in crude oil prices. Since 2000, short distance rates in the US are up 42 percent and long-haul rates by 68 percent. Similar dynamics have played out in developed nations across the world.

Truck rates per mile in the US, 2000-2021. Source: USDA Agricultural Marketing Service

Climate change impacts

Aside from energy costs, weather and other uncontrollable factors have increasingly driven food price inflation and volatility in recent decades. Globally, the incidence of severe weather events affecting agricultural regions has increased steadily since the 1990s, if not earlier. Droughts and hurricanes in the US and floods in China and Australia are recent examples of weather conditions that have reduced food supply and increased food prices and uncertainty. Pests and diseases are also factors. For example, citrus greening – one of the most serious citrus plant diseases worldwide – has reduced orange production considerably in the US.

Finally, while COVID-19 created unique issues with the labour force in the food manufacturing and retailing industries, underlying issues existed throughout the food sector long before the pandemic. Turnover reflects a lack of employee retention and companies seek to minimise it, as it is costly and creates loss of institutional knowledge and skill in the workforce.

According to the US Census, turnover has increased more than 32 percent in food manufacturing since 2011, and over 52 percent among grocery stores. In the US agricultural production sector, across fruit, vegetables, cattle and hogs, new hires are down 33 percent since 2001 and 17 percent since 2011, reflecting a shrinking workforce tasked with feeding a growing population.

Naturally, the question on the minds of many is what can be done to combat these issues. Short-term solutions are scarce, but the burgeoning local food movement improves food access, particularly in rural areas, and consumers would do well to consider farmers markets and other direct-to-consumer outlets as supplements to the supermarket. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted issues with supply chain rigidity and both public and private interests should work to ensure that food can flow between the retail, foodservice and institutional marketing channels with minimal burden. The extent of food loss and food waste in the US and other developed nations remains high, yet a combination of consumer education and improved industry practices can address this to expand the food supply and reduce costs. One illustration of this is the use of imperfect produce in food retail. Rather than throw away fruits and vegetables that are not aesthetically fit for the produce section, these foods can and should be used in-house for party trays, smoothies, baked goods and other value-added and higher margin options for consumers.

A remedial roadmap

Longer term, there are four major components to a strategy that can ensure safe, bountiful and affordable food for the planet. The first is vertical farming and other forms of indoor, controlled production. Vertical farming shows promise for greatly increasing yield and productivity for crops with significantly reduced soil and water inputs. Food can be grown in settings where temperature is carefully controlled, and crops are protected from threats such as severe weather, pests and diseases.

The second is the expansion of renewable energy use in the food supply chain. Vertical farming is highly energy intensive and renewables such as solar and wind, which are decreasing in cost and increasing in efficiency, help address this concern. Perhaps more importantly, renewables will significantly decrease the impact of surging and volatile crude oil prices on food prices and availability around the globe. From electric tractors to solar panels in supermarket parking lots, the potential to implement renewable energy in agribusiness is enormous.

The third is automation and mechanisation. As labour increasingly constrains food production, manufacturing and retail sale, it is becoming clear that we need machines to do more of the work required to get food from the farm to our plates. Of course, technology has driven incredible increases in productivity and efficiency in the past couple of generations. Yet many processes in the supply chain, ranging from fruit packing to animal processing, are often carried out by human hands and could be done quicker and at lower cost via investments in machine technology. This notion is perhaps most salient with respect to driverless trucks, which are currently being used in limited capacity by large firms such as Walmart in the US.

Finally, technology such a blockchain has the potential to dramatically improve traceability in the food supply chain and therefore contain the impacts of food safety events. Currently issues related to foodborne illnesses often result in the largescale destruction of crops or animal inventories. If we are consistently able to identify where our food originated from, and each step it took along its route to our homes or restaurants, we can isolate the source of issues and address them directly without engaging in costly food loss, which results in shortages and higher prices.

The successful implementation of these solutions will take time, money and public-private coordination and collaboration. There will be bumps on the road and food prices will likely remain higher than normal through at least 2023, given our current situation. But we have a roadmap to creating a food supply chain that is resistant to the greatest threats it currently faces, and for the most part the technology required to make it a reality is already here. There is reason for optimism looking forward.

About the author

After finishing his PhD, Richard Volpe spent four years working as an economist at the USDA Economic Research Service in Washington DC. While there he researched a variety of topics, including food price formation, competitiveness in the food industry, and the healthiness of grocery purchases in the US.

Ricky was also responsible for forecasting retail food price inflation at the national level. Now at Cal Poly, Ricky teaches courses on food retail and supply chain management, transportation and logistics and data analysis.

Related topics

COVID-19, Food Security, Recruitment & workforce, retail, Supermarket, Sustainability, The consumer, Trade & Economy