Food industry is perfectly placed to meet phosphorus challenge

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Posted: 31 August 2022 | Professor Bryan Spears | No comments yet

Are you aware that the world’s phosphorus cycle is one such issue that’s wreaking far-reaching havoc? Professor Bryan Spears at the UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology explains what the food industry can do to help.

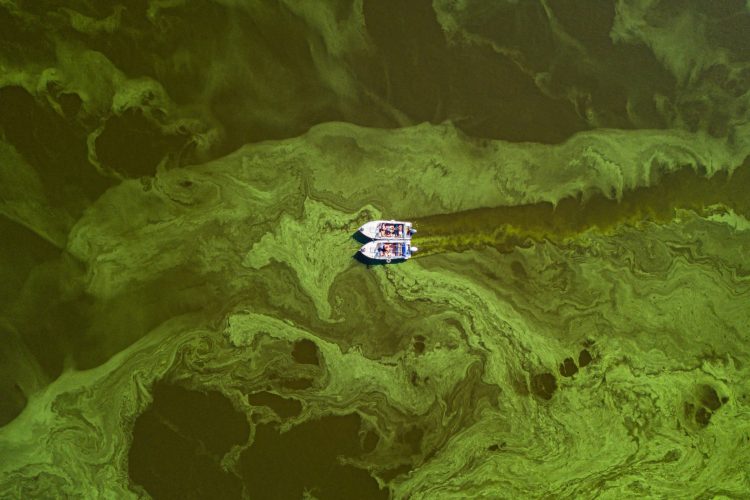

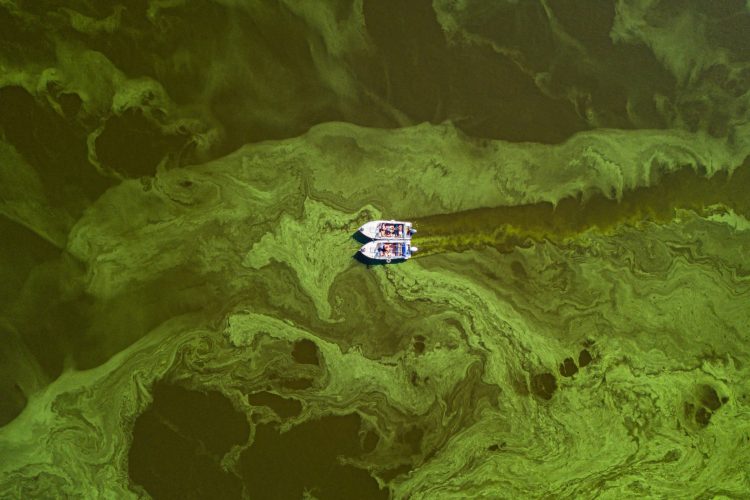

Millions of tonnes of phosphorus is lost to lakes and rivers across the world each year, creating damaging algal blooms

We are living in unusual times when discussion of fertilisers wanders off BBC Radio 4’s Farming Today and into daily news bulletins reporting on the cost-of-living crisis.

However, few of those news reports mention the 300 percent rise since 2020 in the price of phosphate rock, from which phosphorus – a key ingredient in fertiliser – is extracted. Energy costs, the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian-Ukraine conflict have all been implicated in the surge of fertiliser prices.

Phosphorus at the centre of key issues

Of course, food producers and their customers will be acutely aware of their exposure to such price spikes. Food inflation is running ahead of the already significant price rises across the global economy. However, you might be surprised to hear that a large proportion of the phosphorus in the food system is lost (from the anthropogenic cycle). This places phosphorus at the heart of two major global sustainability issues – food security and water quality.

Poor access to phosphorus fertilisers impacts food security – it is estimated that one in seven smallholder farmers cannot afford sufficient fertilisers to sustain food production. Meanwhile, overuse of fertilisers in some countries, together with sewage pollution, sees millions of tonnes of phosphorus lost to lakes and rivers across the world each year.

The visible evidence of this nutrient (ie, phosphorus and nitrogen) pollution is the growth of harmful algal blooms in rivers and lakes, mass fish kill events in heavily impacted ecosystems and disruption to drinking water supplies. In a recent analysis, the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) suggested that “quite likely for most countries, reducing nutrient release and transport will have the greatest positive impact on water quality”.

Why can’t we fix things?

So, why can’t we get a handle on this problem? Well, as always, the answer is – it’s complicated. The supply of phosphate fertilisers is dominated by just four countries who together produced 72 percent of the global output of phosphorus in 2021: China (39 percent), Morocco (17 percent), the US (10 percent), and Russia (six percent).1 Global reserves of phosphate rock are located in regions where geopolitics adds to an already unstable market.

Given the complex nature of the food system in many countries, the environmental impact of poor phosphorus management is often displaced. This is because of international trade in food and non-food goods, where production and consumption occur across borders. Half of the freshwater damage linked to phosphorus between 2000 and 2011 was borne by eastern Europe, Asia and the Pacific regions. In affluent countries, every one percent increase in GDP results in a one percent rise in the harmful impact of phosphorus.

These issues are undoubtedly challenging, but a new report, ‘Our Phosphorus Future’, sets them out in detail and offers some solutions, including for food manufacturing industries. The report draws on the expertise of some 40 international experts from 17 countries, and proposes an overarching challenge for governments and industries to consider adopting a ’50, 50, 50 goal’. This aims at a 50 percent reduction in global phosphorus pollution and a 50 percent increase in recycling of the nutrient by the year 2050.

The benefits of achieving such a goal are significant. The recovered phosphorus would be sufficient to feed more than four times the current global population, representing an estimated $20 billion saving in annual phosphorus fertiliser costs, and would contribute to reducing pollution clean-up costs estimated at $300 billion.

Achieving a significant reduction in phosphorus would also result in billions of dollars in fertiliser savings

The report sets out priority actions with relevance to the food manufacturing industry. These include: improving assessment and reporting of industry phosphorus footprints, promoting the use of fertilisers that contain recycled phosphorus, optimising animal diets to reduce phosphorus excretion, improved use of manures, supporting freshwater clean-up initiatives, and promoting a shift in consumer demand towards more sustainably produced products.

The food manufacturing industry is a hotbed of innovation and has an important role to play if we are to close the loop on the phosphorus cycle.

Nevertheless, businesses who have not started to innovate on nutrient sustainability will soon be spurred on by emerging legislation in some countries, with a focus on increasing recycling, reducing waste, and halting environmental degradation. For example, the 2020 European Green Deal and its flagship Farm-to-Fork Strategy provides ambitions requiring a 50 percent reduction in nutrient losses by 2030.

Many of the recommendations for the food industry within Our Phosphorus Future will potentially deliver savings rather than require additional spending or investment. The obvious one is limiting food waste, which will reduce demand for crops and animal products and therefore phosphorus. The UNEP estimates that, globally, households, retail establishments and the food service industry waste 931 million tonnes of food each year.

New report demands government action to reduce phosphorus pollution

Where does phosphorus fit in your sustainability strategy?

As a society, we are now much more aware of the virtues of recovery, re-use and recycling. Many companies also recognise the benefits of a circular economy approach, yet remain blind to their impact on nutrient sustainability. For example, companies now consider energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions within Net Zero policies. However, few may be aware that accounting systems are also available to assess their phosphorus (and nitrogen) use efficiency, from process to company scales.

New businesses are emerging, and others are adapting to support companies in improving their phosphorus use. They can help food and drink manufacturers identify where leaks in the system can be plugged, so companies can reduce their exposure to price spikes in raw materials, as introduced at the outset, and reduce the environmental impact of their operations. Would Net Zero phosphorus be an achievable goal for your company?

For example, advances have been made in phosphorus recovery and re-use (eg, in recycled phosphorus fertilisers) from the food production system and wastewater. Knowledge exchange networks are already established to support companies in improving their phosphorus stewardship. For example, the European Sustainable Phosphorus Platform fosters engagement across all actors of the food value chain.

Some UK food manufacturers are already using anaerobic digesters to provide waste streams as raw materials that can be turned into fertilisers and for the production of energy through biogas.

They can also review their own phosphorus production footprint, just as they measure their carbon footprint. Where necessary, they can look to revamp their supply chains to ensure they are sourcing raw materials with a low-phosphorus footprint.

The food manufacturing industry is perfectly placed to lead the way in responding to the global phosphorus challenge. In doing so, cost savings and new business opportunities will emerge. Shaping consumer choice will be key; the talent provided by corporate sustainability and marketing teams has never been more important.

References

1. Jasinski et al, 2022

About the author

Bryan is a freshwater scientist at the UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, an independent not-for-profit research institute, and is one of the lead authors of the new ‘Our Phosphorus Future’ report. His work focuses on the study of lakes, rivers and estuaries and their responses to changes in climate and land use.