Cleaning programmes and coronavirus control – what lessons have we learnt?

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Posted: 6 May 2021 | John Holah | No comments yet

John Holah, Principle Corporate Scientist at Kersia, reflects on the impact that the Covid pandemic has had on cleaning and hygiene practices in the food industry and considers the potential future benefits.

Prior to undertaking a cleaning programme for food processing equipment, a number of factors should be considered. Firstly, the objective of the cleaning programme should be determined. This could include the need to remove visual soiling for organoleptic reasons or brand protection issues such as different meat species, the need to control food spoilage microorganisms, or the need to control hazards such as allergens or pathogens.1

Secondly, a risk assessment should be undertaken to assess the choice of cleaning chemicals and application techniques required. This should include the chemical nature of the food soil and the food processing conditions that have led to its formation, the chemical compatibility of the equipment and environmental surface materials, the hardness of the water supply, the application method (manual, automated or CIP), the rinsing method and pressure, and any impact on effluent treatment plants that may be present.

Thirdly, more practical aspects should be considered such as length of cleaning window available and costs. Following these considerations, a cleaning method and chemicals can be chosen that meet the programme’s cleaning objectives, and that have minimal impact on other food processing and environmental activities.

The current COVID-19 pandemic has done nothing to change these considerations (the original cleaning objective must still be met) and to thus attempt to change current food processing equipment cleaning programmes, without due consideration, may be counterproductive. In addition, the recommendations from the WHO,2 CDC3 and EFSA4 remain that there is no evidence that COVID-19 is transmitted by food or its packaging.

What has changed with COVID-19, however, is the need to consider additional environmental and personal hygiene measures. These are primarily to prevent person-to-person transmission via touching fomites that could have been contaminated from an asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic COVID-19 case. This is particularly important as recent studies have suggested SARS-CoV-2 survival is extended on surfaces, particularly at low temperatures, eg, a decimal reduction time of 163 hours at 4°C.5

Additional measures have included:

- surface disinfection for frequently touched environmental surfaces; eg, door handles, handrails, light switches, machine interface points) during production

- surface disinfection for potential virus hot spots; eg, floors, where expelled droplets will settle and potentially survive

- more frequent hand hygiene procedures, particularly after touching frequently touched surfaces or viral hotspots; eg, washing hands after touching the floor or when removing/changing footwear

- COVID-19 decontamination procedures for food processing and ancillary areas following confirmation of the presence of COVID-19 cases working in these areas.

It may, however, be prudent to ask the question of whether current detergent and disinfectant-based cleaning programmes for food processing equipment have any effect on SARS-CoV-2. One of the lessons we have learnt about the control of COVID-19, that has been well broadcasted to the public,6 is that “washing your hands with soap and water dissolves the virus”, which is based on established facts.7 Some detergents may, therefore, influence coronaviruses.

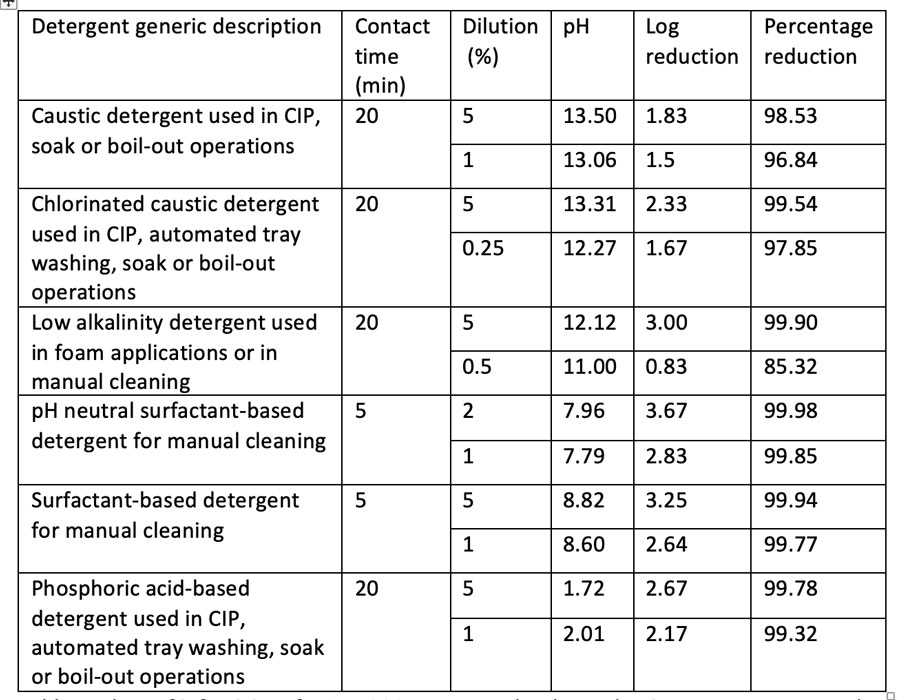

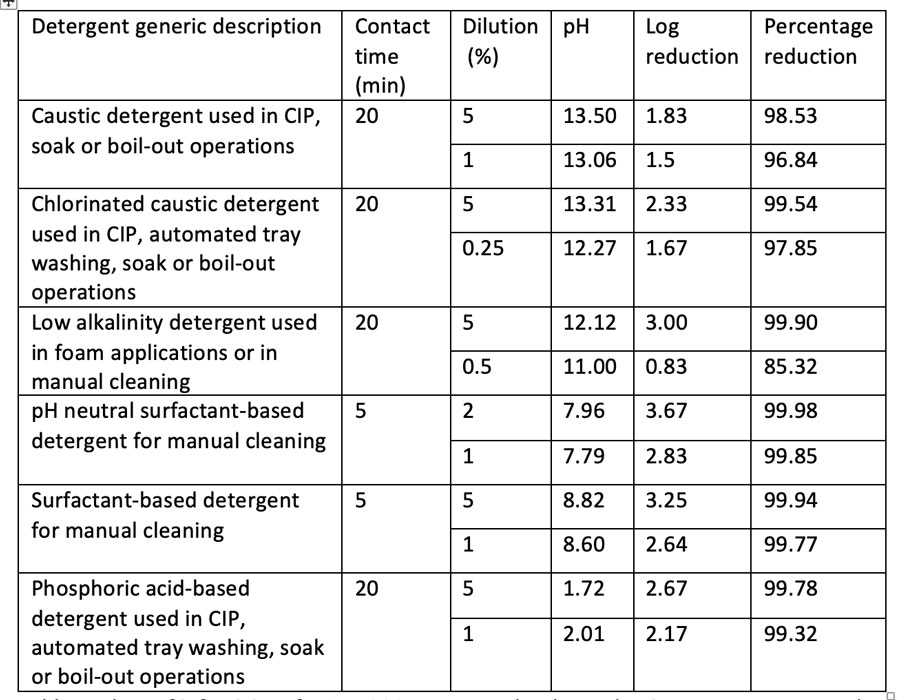

Holchem has commissioned studies to assess the effect of a range of Holchem detergents on coronaviruses with the Perfectus Biomed Group (Daresbury, Cheshire, UK). Six detergents were chosen to reflect the type of detergents commonly used in the food processing and food service industries, to include caustic, alkaline, neutral and acidic products. The detergents were tested against the human coronavirus strain HCoV-299E using the method of the European virucidal disinfectant test EN 14476, under dirty conditions, according to their recommended concentrations and contact times.

All of the detergents showed virucidal affects (Table 1), with a range of between 1.5-3.67 log orders of loss of infectivity (96.8-99.98 percent reduction) within their in-use concentrations. The surfactant-based products were the most effective, within their five-minute contact times, rather than the extended contact times (20 min) of the caustic and acidic products. The acidic product was more effective than the caustic detergents.

Any virucidal activity realised in practice from detergents, however, will be inconsistent and will depend on the level of soiling present on the surface. Detergency, however, will have some role in reducing the presence (removal) and infectivity of (remaining) coronavirus, particularly after much of the soiling present has been removed from the surfaces. However, as disinfection is only ensured following cleaning, this work emphasises the need for disinfection (following detergent application) to further reduce the infectivity of any viral particles present.

Table 1: loss of infectivity of HCoV-299e expressed as log reduction or percentage reduction, following exposure to a number of detergents

As coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2, are enveloped viruses, they are the least resistant to disinfectants of the microorganisms found in food establishments.8 In addition, the effectiveness of disinfectants on coronaviruses is well documented; eg, sodium hypochlorite and alcohol,9 QATS, sodium hypochlorite, hydrogen peroxide and ethanol.10,11Specific disinfectant product performance claims can be made for virucidal activity against the European disinfectant test, EN 14476, which requires a 4-log reduction of infective viral particles in five min. Disinfectants used for additional environmental decontamination (as advocated above) and decontamination following any known COVID-19 cases, must be EN14476 approved.

Holistically, the detergency studies and general knowledge on viral disinfection enhance our knowledge of the overall potential of routine processing equipment cleaning and disinfection programmes to meet their established cleaning objectives, while providing additional assurance that they are also controlling SARS-CoV-2.

Looking to the future, hopefully, the additional practices the food industry has undertaken associated with environmental surface disinfection and enhanced hand hygiene have helped in their intended COVID-19 control. Collectively, these measures perhaps represent the biggest change in hygiene practices within the food industry for many years. Is it possible that these changes could also have brought additional benefits in terms of food safety or personal health? Fewer microorganisms in the food process environment (including operatives’ hands) might lead to reduced levels of general microorganism indicators (TVC, Enterobacteriaceae) and reduced levels of environmental pathogens, particularlyListeria, via cross contamination in food products. This could lead to enhanced product safety, quality (reduced spoilage), improvements in shelf life and fewer customer complaints. Fewer other, non-SARS-CoV-2, respiratory viruses on operatives’ hands could also lead to fewer cases of respiratory diseases (colds and flu) resulting in less absenteeism.

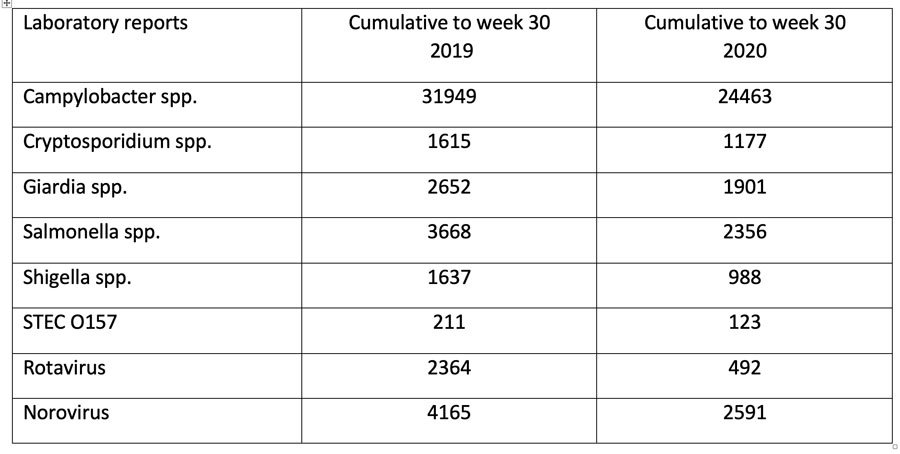

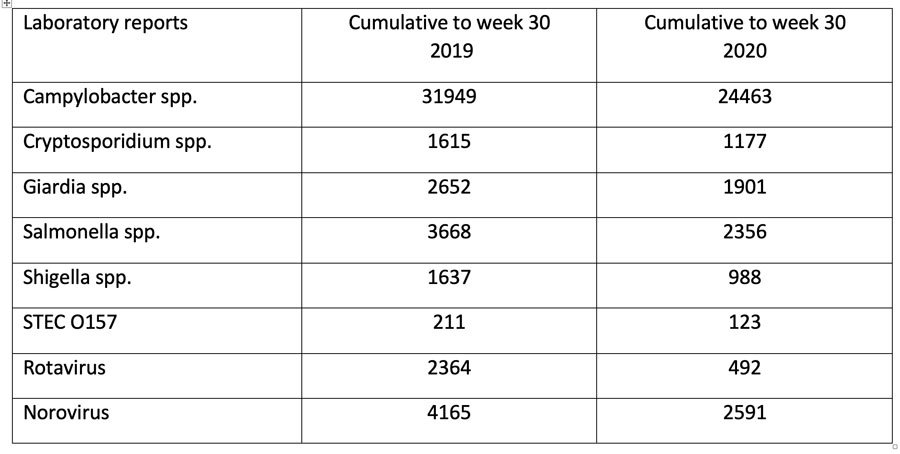

Is there any evidence of enhanced food safety? In the wider community, Public Health England12 published cumulative data up to week 30 for common gastrointestinal infections in England and Wales (Table 2).

Table 2: Cumulative laboratory reports of common gastrointestinal infections in England and Wales reported to Public Health England to week 30 for 2019 and 2020

Table 2 shows that the general incidence of gastrointestinal infections in the population was approximately one third lower in 2020. Similarly, the number of Listeria recalls alerted by the UK Food Standards Agency (FSA) in 2020 (six cases) was slightly lower than in 2019 (seven cases). This position is not unique to the UK as other countries have also shown a reduction in pathogen incidence in the community, typically reported in Food Safety News,13 including Finland, the USA and Australia.

The reasons for the reduction in cases of gastrointestinal illness in the population is complex. Perhaps not as many cases of illness have been reported due to difficulty in accessing GPs (and therefore fewer stool tests), or people are not eating outside the home in restaurants so much, or the diet of people spending more time at home has changed? There may also be changes in the food factory or the manufacturing procedures that might enhance food hygiene; for example, reduced food product volumes, fewer product SKUs, fewer staff, increased use of gloves, and longer hygiene windows to enable enhanced cleaning. Equally, the opposite may be true, with food manufacturers increasing production, particularly at the start of the pandemic, with an increased pressure on maintaining hygiene windows.

It would be very useful, therefore, for both individual food manufacturers and the industry at large, to try and gain evidence from food industry data to see if these major changes in food hygiene practices have had additional benefits to food safety or personal health. Perhaps the biggest lesson that we have learned is that the higher the hygiene standards practised, the greater the food safety benefits. In essence, should our current, extended cleaning and disinfection practices become the new, post-COVID-19 pandemic, norm?

John Holah

From January 2021, John became the Principal Corporate Scientist-Food Safety and Public Health for the Kersia Group, having been the Technical Director at Holchem Laboratories Ltd prior to the acquisition of Holchem by Kersia. Prior to this John spent most of his working life at Campden BRI where he was Head of Food Hygiene, for more than 20 years.

John is also an Honorary Professor in Food Safety and Hygienic Design at Cardiff Metropolitan University.

He has supported the works of the European Hygienic Engineering Design Group (EHEDG), International Association of Food Protection (IAFP) and the Global Food Safety Initiative (GFSI) for many years, has chaired various ISO and CEN committees on hygienic design and chemical disinfection and sat on government committees on food safety and hospital acquired infections.

References

- Holah J. (2018). Cleaning and Disinfection Objectives. Reference Module in Food Science. Elsevier, pp. 1–7. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-100596-5.21203-1 ISBN: 9780081005965

- WHO1 (2020) Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Food safety and nutrition. https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/coronavirus-disease-covid-19-food-safety-and-nutrition

- BS EN 14476:2013+A2:2019 Chemical disinfectants and antiseptics. Quantitative suspension test for the evaluation of virucidal activity in the medical area. Test method and requirements (Phase 2/Step 1) CDC (2020) Food and Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/daily-life-coping/food-and-COVID-19.html

- EFSA (2020) Coronavirus: no evidence that food is a source or transmission route. https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/news/coronavirus-no-evidence-food-source-or-transmission-route

- Guiellier, et al. (2020) Modeling the inactivation of viruses from the Coronaviridae family in response to temperature and relative humidity in suspensions and on surfaces. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 86; (18) e01244-20

- WHO2 (2020) Save lives: clean your hands in the context of COVID-19. https://www.who.int/infection-prevention/campaigns/clean-hands/WHO_HH-Community-Campaign_finalv3.pdf

- Sickbert-Bennett EE, Weber DJ, Gergen-Teague MF, Sobsey MD, Samsa GP, Rutala WA. (2005) Comparative efficacy of hand hygiene agents in the reduction of bacteria and viruses. Am J Infect Control, 33: 67-77

- McDonnell G, Russell DA. (1999) Antiseptics and disinfectants; Activities, Action, and Resistance. Clinical Microbiology, Jan. 1999; P. 147-179

- WHO3 (2020) Which surface disinfectants are effective against COVID-19 in non-healthcare setting environments. https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/coronavirus-disease-covid-19-cleaning-and-disinfecting-surfaces-in-non-health-care-settings

- Ijaz MK, et al. (2020) Microbicidal actives with virucidal efficacy against SARS-CoV-2 and other beta- and alpha-coronaviruses: implications for future emerging corona viruses and other enveloped viruses. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7246051

- Han S, Roy PK, Hossain MI, Byun K-H, Choi C, Ha S-D. (2021) COVID-19 pandemic crisis and food safety: Implications and inactivation strategies. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 109: 25-36

- PHE (2020) Routine reports of gastrointestinal infections in humans (England and Wales): June and July 2020 Health Protection Report Volume 14 Number 15 25 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/…

- FSE (2020) Food Safety News articles: –

- https://www.foodsafetynews.com/2020/06/australia-sees-decline-in-campylobacter-and-salmonella/ https://www.foodsafetynews.com/2020/06/decline-in-foodborne-outbreaks-likely-due-to-covid-19-measures/

- https://www.foodsafetynews.com/2020/11/e-coli-outbreaks-with-unknown-food-sources-top-light-year-for-foodborne-illnesses/

- https://www.foodsafetynews.com/2021/01/researchers-assess-impact-of-covid-19-measures-on-foodborne-infections/

- https://www.foodsafetynews.com/2021/02/covid-19-measures-accompany-decline-of-foodborne-infections/

Related topics

Contaminants, COVID-19, Food Safety, Hygiene, Processing, Regulation & Legislation, Sanitation