The listeriosis outbreak in South Africa: what have we learnt?

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Posted: 21 November 2018 | Lucia Anelich | No comments yet

When the Minister of Health announced at the end of last year that South Africa was in the midst of a listeriosis outbreak, the source was still unknown and the country ill-prepared for such a devastating crisis. In the first of a two-part feature, Dr Lucia Anelich shares her expert perspective.

The largest documented listeriosis outbreak in history is over.

The South African Minister of Health, Dr Aaron Motsoaledi, made this announcement at a press conference held in Johannesburg, South Africa, on 3 September 2018. The outbreak officially resulted in 1,065 confirmed cases and 218 deaths and was first announced publicly on 5 December 2017, by which time 550 cases and 36 deaths were already confirmed. In March 2018, the Minister of Health declared that the source of the outbreak originated at a specific processed meat manufacturing facility. There then followed chaos for all involved, including producers, manufacturers, distributors, suppliers, retailers, consumers and laboratories, as well as various national authorities. Consumers refused to eat any products associated with the specific brand and other non-implicated brands that resembled any cooked, frozen or raw processed meats, or any products that contained similar ingredients. As a result, tons of processed meat products were returned to manufacturers and retailers.

The death toll from the listeriosis outbreak of 218 may in fact be far higher for many reasons, including under-reporting due to, for example:

- Affected individuals not seeking medical treatment, particularly in rural areas

Unawareness amongst health-care workers, mainly in rural areas - The elderly dying in retirement homes/frail-care facilities where there was little awareness of the outbreak or information on implicated products and typical symptoms to look out for in the elderly

- Miscarriages and stillbirths due to listeriosis that were not recorded

- Affected products exported to other countries in Africa that do not have the capacity to conduct foodborne disease surveillance, monitoring activities or deal with food safety-related emergencies.

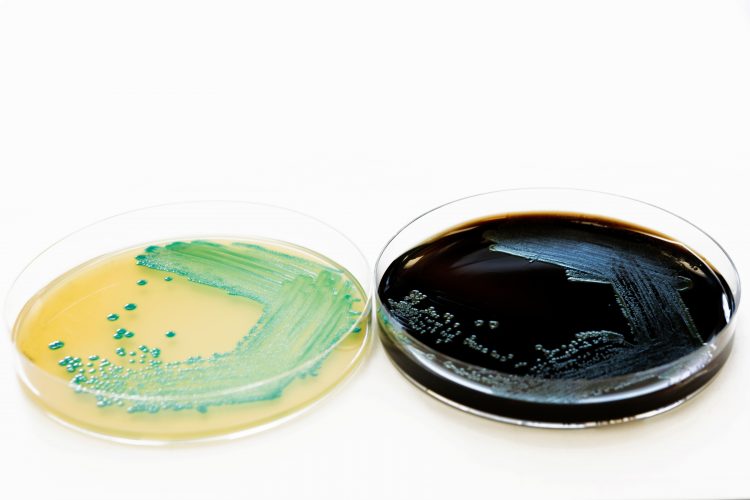

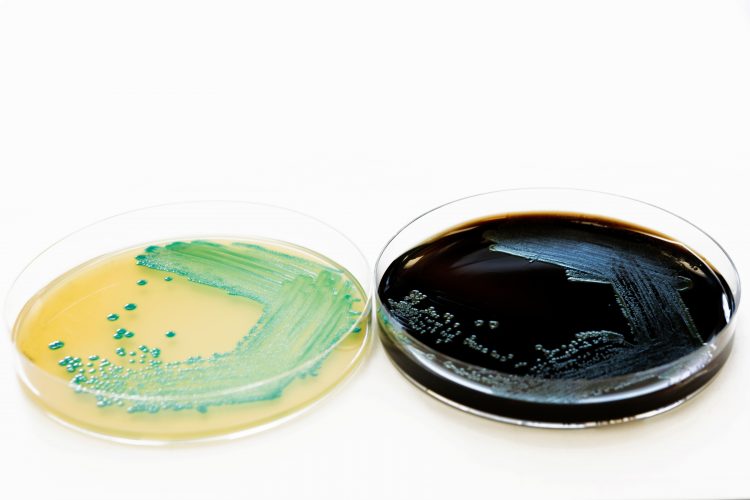

Listeria monocytogenes is a foodborne pathogen that causes the disease known as listeriosis. It is a relatively rare disease but it causes 20-30 percent mortality when it strikes, which is one of the highest known death rates for foodborne pathogens. Social and economic impact is therefore high.

Two forms of listeriosis occur:

Febrile gastroenteritis (mild and usually self-limiting within a few days). Symptoms are similar to other foodborne diseases and unless specifically diagnosed as listeriosis, the affected person would most likely not know he/she was infected with L. monocytogenes, therefore this form of the illness is most likely under-reported.

Symptoms include:

- Fever

- Watery diarrhoea

- Nausea

- Headache

- Pains in joints and muscles.

This type of illness normally occurs 24 hours after ingesting the food containing high levels of L. monocytogenes [>105 colony forming units per gram (cfu/g)]. Symptoms however can appear as soon as six hours or as late as 10 days after ingestion of the contaminated food. The illness usually lasts two days, but can last up to one week.

Invasive listeriosis is the severe form of the disease and causes septicaemia, meningitis and encephalitis. Symptoms appear between three to 70 days after ingestion of the contaminated food. In some cases, symptoms can appear as quickly as the following day and as late as 90 days later.

Symptoms are:

- Headache

- Fever

- Stiff neck

- Confusion

- Loss of balance

- Convulsions

- Muscle aches

Invasive listeriosis affects mainly the susceptible sectors of the population, ie pregnant women – usually contract flu‑like symptoms; mainly self-limiting. The woman transmits the microorganism via the placenta to the foetus possibly resulting in:

- Miscarriages

- Pre-term delivery with associated complications

- Still births

- Births with neonates exhibiting septicaemia, encephalitis, meningitis.

- Elderly >65 years (can be lower)

- Immuno-compromised individuals, for example: HIV+ individuals, cancer patients, persons with auto-immune diseases (suppression of immune system due to cortisone and other treatments), diabetics, organ transplant patients.

The invasive form sometimes affects young healthy adults, resulting mainly in brain-stem encephalitis.

The South African outbreak was quite different to outbreaks that have been recorded in the developed world as it affected mainly neonates (babies <28 days old) ie, 93 neonate deaths of the total 218 deaths were recorded. In outbreaks in developed countries, the affected groups were the elderly or a specific category of cancer patients in hospitals where outbreaks have occurred. L. monocytogenes is now the second most frequent cause of bacterial meningitis in South Africa.

South Africa was ill-prepared for this outbreak, but as a result, many lessons were learned. Business as usual, in the broadest sense of the phrase, is not an option. It is incumbent on all of us in South Africa, both in the public and private sectors, to implement necessary changes to improve the food control system in the country and to improve food safety management in its broadest sense, to ensure that this magnitude of outbreak does not happen again. If we do not heed this warning, then 218 lives will have been lost in vain.

Lesson One: the impact of a fragmented food control system

The outbreak highlighted the weaknesses in the fragmented food control system in South Africa. There is a lack of coordination and communication between the three main national departments with a food-safety mandate, with consequential problems impacting industry directly. Each of these national departments functions in a different manner, with some faring better than others. Monitoring of food products on the market is generally not conducted by national authorities and where it may occur, it is uncoordinated, non-transparent and none of the results are shared with stakeholders and the public, as there is no central database in place.

This situation made it difficult to understand which foods could possibly be implicated in the outbreak, which may have resulted in a delay in finding the source.

Externally-funded projects have occurred since 1997, with a number of reports submitted to government identifying many gaps in the fragmented food control system accompanied by proposals for structural changes. None of these was adopted as there was little focus on food safety at national authority level, with the food industry in the country largely self-regulated. There is currently a call for a National Food Control/Food Safety Authority (FCA) in the belief that this will be a panacea for all South Africa’s food safety problems. However, if a central FCA were to be established, it would need to be structured with clearly delineated functions, roles and responsibilities: it should be apolitical with the focus on protecting the health of the consumer and facilitating trade. More importantly, it should have a firm commitment from government to provide adequate resources, both human and financial. If these aspects are not considered at the very least, South Africa will be exchanging one weak food control system for another – the only change will be cosmetic. Substantial investment is required to develop government laboratories specialised in food safety.

Fragmented communication during the outbreak was magnified by the introduction of a fourth role-player, the National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD), which created further confusion in industry. The NICD began detecting an increase in numbers of listeriosis cases early in 2017. It was due to its intensive investigations and associated laboratory capacity (including its ability to apply Whole Genome Sequencing technology), that the outbreak was detected and attributed to the Multi Locus Sequence Type ST6, which was later traced to a specific polony manufacturer in the country, Tiger Brands.

Lesson Two: lack of regulated standards for listeria monocytogenes in at-risk foods

The Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act 54 of 1972 is the main act dealing with the safety of foods and beverages falling within the mandate of the National Department of Health. R692 covers Regulations Governing Microbiological Standards for Foodstuffs and Related Matters. Despite a number of calls to government over the years from food safety specialists in the country to include a maximum permitted level for L. monocytogenes in applicable foods in these regulations, this did not happen. Consequently, to date, there is no regulated maximum permitted level for L. monocytogenes in ready-to-eat (RTE) foods in particular. The outbreak has, however, galvanised government to revise these regulations accordingly, and these should be finalised soon.

Lesson Three: the importance of coordinated responses

The announcement of the source of the outbreak was made by the Minister of Health on 4 March 2018. This resulted in immediate extensive recalls of products manufactured by the implicated company, Tiger Brands, including non-polony meat products, both RTE and non-RTE, as a precaution.

South Africa was ill-prepared for this outbreak, but as a result, many lessons were learned.

This caused widespread panic among consumers, as the Minister’s announcement did not provide any information on how they should deal with implicated product in their homes. This was communicated only later. In the meanwhile, many consumers disposed of their products in municipal bins, which landed on landfill sites. Landfill sites in South Africa are full of ‘waste pickers’ who salvage what they can for re-sale; most of these waste pickers are not food secure and they were consuming discarded products and sharing them with others. This drove home yet another lesson: the need for coordination of all relevant role-players before such announcements are made, to ensure that important activities are coordinated and that accurate, understandable information in different languages is communicated to the public via a variety of media in a timely and organised fashion. Experts in the field of communicating risk to the consumer are critical to the success of this process.

Listeria monocytogenes is a foodborne pathogen that causes the disease known as listeriosis.

The National Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA) was tasked with ensuring appropriate destruction of the products and initially had no information on the organism, what it does, what the risks are, under which conditions it survives, how it could be destroyed etc. It therefore took time to determine how the recalled food would be disposed of. There was a realisation, too, that South Africa does not have the capacity to destroy the volume of food involved all at once. Consequently, the DEA developed a range of interventions, including incineration and autoclaving at healthcare waste treatment facilities and incineration in cement kilns that operate at over 800°C. Disposal at Class A landfill facilities, within a trench at the landfill after pre-treatment with caustic soda or an equivalent, with immediate closure of the trench was another intervention employed. To date, 5,897 tonnes of food have been destroyed.

Lesson Four: impact of over-reaction

The National Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF) is responsible for regulating raw meat and poultry, among other commodities. The listeriosis outbreak has resulted in the desire by DAFF to regulate L. monocytogenes in raw red meat and poultry, including offal, to a level of ‘absent in 25g’. The same level of ‘absence in 25g’ is desired for non-pathogenic Listeria spp in these same commodities. These requirements are not based on risk and are an over-reaction to the listeriosis outbreak. This is underscored by a recent in-depth review of other countries’ standards for raw meat and poultry in which no requirements are included for L. monocytogenes or non-pathogenic Listeria spp. The requirements will serve neither the industry, nor the consumer well. Poultry is a cheap form of protein for many consumers in South Africa; the additional controls that raw poultry plants would need to implement to achieve absence in 25g will come at a cost to the consumer, negatively affecting food security in the country, without necessarily providing greater protection to the consumer.

About the author

Lucia Anelich holds a PhD in Microbiology. She spent 25 years in academia, as HOD: Biotechnology and Food Technology and Associate Professor at the Tshwane University of Technology. In 2006 she joined the Consumer Goods Council of South Africa where she established a food safety body for the South African food industry, a first for the country. In 2011, she started her own national and international food safety consulting and training business. She served as Extra-Ordinary Associate Professor at Stellenbosch University for the period 2011-2014.

Issue

Related topics

Food Safety, Food Security, Lab techniques, Outbreaks & product recalls, Pathogens

Related organisations

National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD), Tiger Brands