Analytical governance in the food industry

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Posted: 22 February 2016 | François Bourdichon, Jean François Billet | No comments yet

Quality and Food Safety testing are key elements for validation and verification of implementation of control measures and efficiency of food safety systems.

Unfortunately too often considered simply as a tool for decision making, the scope of the testing scheme is not always considered in as much detail as needed, and the purpose of the testing is often under considered until the laboratory generates unexpected results, i.e. detects a deviation in the food process.

While laboratories, either in-house or external, should be considered as the ‘eyes’ of the factory, one has to make sure they look in the right direction. Specifically, the analysis performed has to be jointly decided between risk assessors and risk managers on a food safety perspective. The laboratory management team needs also to prove the laboratory’s proficiency as a trusted partner to deliver reliable results for robust decision making.

Danone and Mérieux NutriSciences recently communicated on a global food safety partnership. How do two companies share goals and build common trust on such a sensitive topic? How does the analytical strategy of the chemistry and microbiology analytical laboratory fit with their global strategic approaches?

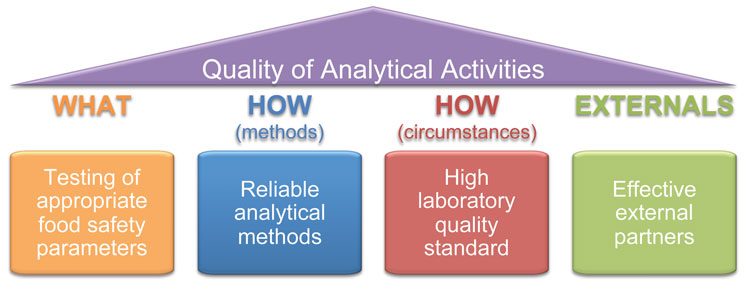

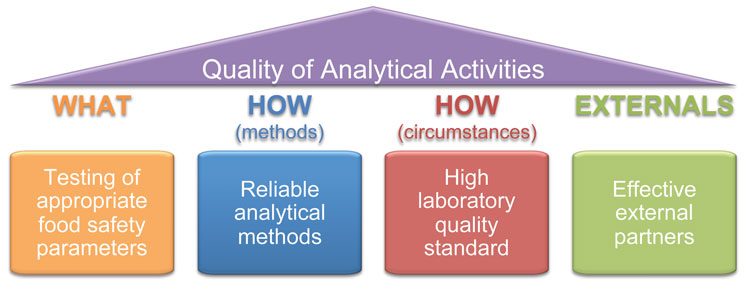

Capacity, capability and expertise of laboratory management

In the strategy of an analytical structure, to make sure the testing is relevant to the decision making, the management must consider the WHAT and the HOW. The WHY is a risk management decision which is not under responsibility of the laboratory per se; the responsibility of the laboratory is to provide a consistent and solid answer to a question, not to assess the relevance of the question (Figure 1).

Three aspects of the laboratory management should be considered: capacity, capability and expertise. They are not necessarily related and should be specifically managed.

Figure 1: The four pillars of analytical governance

Capacity and capability are linked to the physical entity of the laboratory and its management, while expertise is person related and linked to scientific and practical knowledge. While this can be overlooked as a minor, the consequences for business sustainability and contingency planning are quite different: capacity and capability need investment (and space) while expertise needs time (and strategy).

Expertise particularly is sometimes reduced to academic knowledge, where it is also linked to the WHY the testing are performed and highly needed to assess the relevance of the methodology and ensure that the answer provided is fit for purpose.

Surveillance programmes and factory control plans

ISO 9000 and quality management system generally refer to certificate of conformance (CoC) or certificate of analysis (CoA). The laboratory provides indeed testing results and CoA. Yet two major purposes can be made behind testing in the food industry

- Factory control plan for the verification of (effective) implementation of control measures

- Surveillance programme to focus on identified risk foods and contaminants, and gaps in other information being collected.

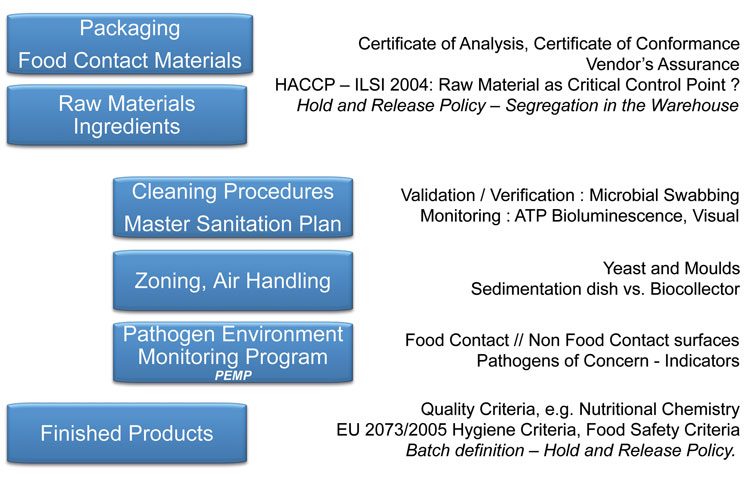

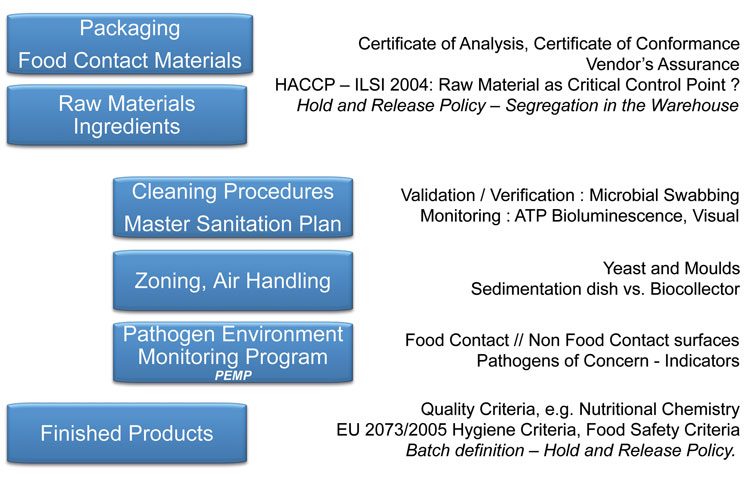

Factory control plans (Figure 2) are used for compliance monitoring.

Figure 2: Factory control plan

Surveillance programmes are conducted to:

- Monitor compliance in relation to new and existing food regulatory measures

- Identify issues of potential importance to public health and safety

- Monitor long-term trends in the levels of hazards in food

- Respond to issues of major community concern.

The right tool for the best purpose

The laboratory serves the risk managers for decision making, as well as the risk assessors for hazard characterisation. It is therefore responsible to ensure the choice of the most appropriate method. Even if it is not its role to decide IF to test, the laboratory is responsible for HOW to test.

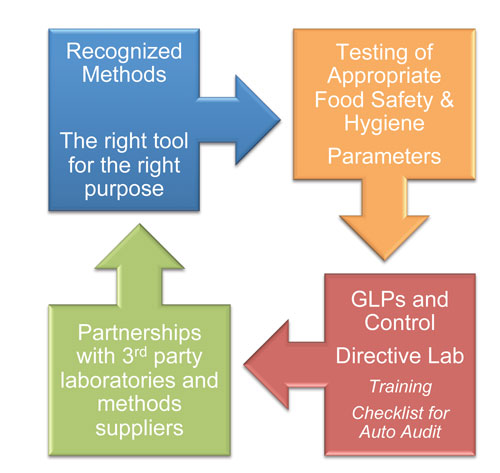

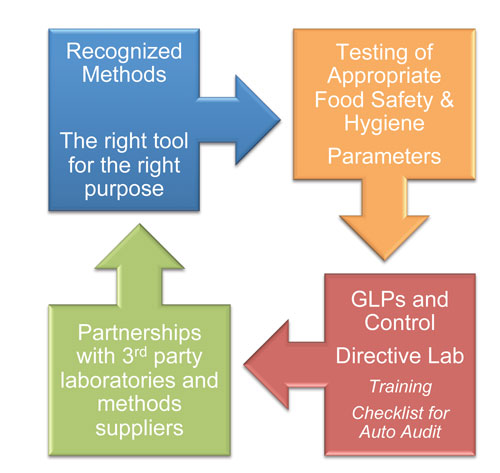

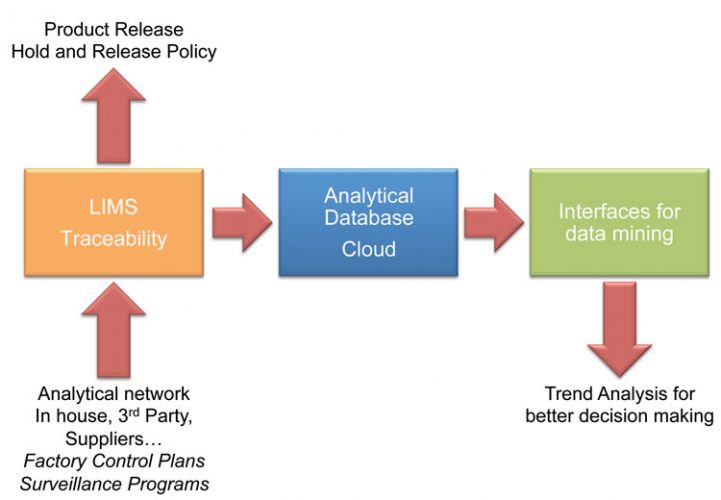

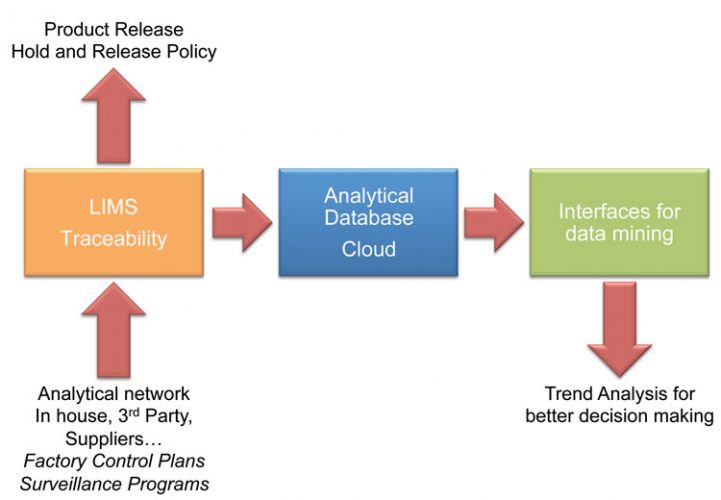

Having the appropriate tools is linked to the initial decision to conduct the test. And based on the historical data and trend analysis, the relevance of the test and eventually its efficiency can be ameliorated. Benchmarking with external existing solutions is also of high relevance. The laboratory is part of a whole improvement process, and should have as any structure continuous improvement in the scope, not only to deliver the most consistent results, but as well the most relevant (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Analytical governance workflow

Good Laboratory Practices: from doubt to trust

Whether external or internal, a laboratory is always challenged upon his capacity to conduct testing. The laboratory also has to be able to continuously show its compliance to perform the analytical method. As for Good Manufacturing Practices to conduct hygienic food processing sites, Good Laboratory Practices are common agreed guidelines and recommendations to manage a laboratory properly.

While specific standards are in place of specific examinations (ISO 7218:2007 for microbial examination, ISO 22174:2005 for molecular detection), the widely recognised golden standard is the ISO/IEC 17025:2005. The methods might be different, but at least laboratories are commonly managed by the same approach, even if the standard can be applied differently worldwide.

Even if accreditation as such is not regulatory binding, working under the scope of accreditation has become a must have – most specifically proficiency testing 2 and personal qualification. To be unchallenged upon its results, the laboratory must have the management settings defined to prove its efficiency.

Global harmonisation of methods

Testing for border control of food products is the historical first rationale for analytical testing. Codex Alimentarius set the rules to define the acceptable methods and sampling scheme 3.

In a globalised world market, the recognition of the methodologies has become a key concern. Harmonisation is highly expected from every stakeholder, but the science behind differs from one world region to another. International standardisation organisations such as ISO, AOAC International, or professional organisations such as ICCO, FIL-IDF work in collaboration to promote a common global validation schemed with mutual recognition.

Science evolves differentially and regulations which define specifications are based on different risk management processes. The methods for decision making often end up being different for a food business operator between the country of processing and the place of market, e.g. for the pathogen adulterant Salmonella spp., different methods such as ISO 6579, FDA BAM or GB4789.4 coexist.

This is also an issue for analytical comparison to do exposure assessment. Global harmonisation of method is expected by every stakeholder, but this turns out to be a continuous endless process.

Generating data; How to make the best out of it?

Laboratories generate a tremendous amount of data. The direct outcome is classically in the food industry either raw material acceptant or finished products release. But rarely, few additional decisions are taken out of these numerous results. Trend analysis unfortunately often remains on the first rank of the wishing list but is not as widely implemented as it should be.

Since the laboratory is not responsible for the rationale to conduct the test, the outcome of the results are in the hands of the global quality management.

To make the best use of quality control (scheduled and routine testing), programmes of Quality Assurance (proactive monitoring and assessment of scheduled component) and Quality Improvement (purposeful change of processes to improve the reliability of achieving an outcome) one must ensure the efficient management of analytical data (Figure 4), from (harmonised) data generation at the laboratory level to data mining for the improvement of monitoring food safety control measures4 (which is somehow the purpose of Principle 6 of HACCP; establish verification procedures).

Figure 4: Analytical data

Externalising the activity: define the rules of the partnership

The Food Industry is a different field to analytical testing. As the strategy for efficient laboratory management requires specific skills and insights, it is often decided by food business operators to externalise the activity to a third party laboratory.

While this does make sense to externalise capacity and capability, expertise is often overseen during this decision. As stated before, this expertise is linked to the experience on conducting analytical testing, but also on the characteristics of the food products and the food process. This knowledge is shared between the two partners.

The analytical provider, whether internal or external, has indeed got to be considered as a partner. Insights on product characteristics and/or food processes that might interfere with a correct analytical workflow should be communicated to the analytical team, and the limits of the method should be communicated to the food business operator e.g. when deciding to test to assess whether or not sulphites are in vegetable food products, testing through total sulphur content only makes sense if sulphites are indeed the only source of sulphur.

Inconclusive results can be generated from an inappropriate testing scheme. When externalising, define the rules of this partnership and take time to make sure the testing scheme make sense vs. the rationale of the decision to test.

Conclusion: know what you are ready to learn from your analytical partner

The Food Analytical Laboratory is ‘only’ responsible for the quality of its results, not from the outcome of them.

Although this is not per se part of the criterion, as specified in the Codex Alimentarius Guidelines for establishment of microbiological criteria related to foods5: “Consideration should be given to the action to be taken when the microbiological criterion is not met and the action should be specified” – be ready to face the unexpected answer, and proactively anticipate non-compliance.

In their partnership between the two companies, Danone and Mérieux Nutrisciences shares different responsibilities. The food safety management system and specifically hazard characterisation, the rationale for taking the decision to test, is within the hand of the food business operator. The capacity and capability, working on emerging technologies and new methodological processes is under the responsibility of the analytical laboratory network. When matching what needs to be verified and monitored vs. what can be identified and analysed, the partnership helps one providing the other the best tools for the most appropriate purpose.

About the authors

François Bourdichon is the Food Safety Analytical Governance Director for Danone. He coordinates the analytical network of Danone’s five divisions; Advanced Medical Nutrition, Africa, Dairy, Early Life Nutrition and Waters.

References

- Danone and Mérieux Nutrisciences. Danone and Mérieux NutriSciences enter into a global food safety partnership. November 2 – 2015.

http://www.merieuxnutrisciences.fr/fr/eng/news/news/danone-and-merieux-nutrisciences-enter-into-a-global-food-safety-partnership/717

http://finance.danone.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=95168&p=irol-newsArticle&ID=2104939 - Wilder, C. The importance of proficiency testing programmes in the food industry. ATCC, 2015.

- Codex Committee on Methods of Analysis and Sampling (CCMAS). Website accessed: http://www.codexalimentarius.org/committees-and-task-forces/en/?provide=committeeDetail&idList=8

- EDES / COLEACP – Handbook 1.13: Food Safety System – Role of laboratories in food safety system

- Codex Alimentarius Committee on Food Hygiene. Principles and guidelines for the establishment and application of microbiological criteria related to foods. CAC/GL21 – 1997 Revised 2013.

The rest of this article is restricted - login or subscribe free to access

Why subscribe? Join our growing community of thousands of industry professionals and gain access to:

- bi-monthly issues in print and/or digital format

- case studies, whitepapers, webinars and industry-leading content

- breaking news and features

- our extensive online archive of thousands of articles and years of past issues

- ...And it's all free!

Click here to Subscribe today Login here