Feeding Asia: The problem with Asia’s population growth for food security

Posted: 16 January 2017 | Roy Manuell | Digital Editor | 1 comment

Part two of New Food’s ‘Feeding Asia’ series looks at how population growth and changing consumption habits are affecting regional food security…

In our introduction to the ‘Feeding Asia’ series during which New Food looks at the growing issue of Asian food security, we introduced at a glance some of the main factors concerning food security in the world’s most populous continent.

Certainly a look at the reality of population growth and regional demography will be extremely important to our discussion, not simply for an analysis of the question of feeding the increasing number of mouths to feed but also with a consideration of the change in Asian consumer habits as a result of socio-economic shifts across the continent.

What goes up…

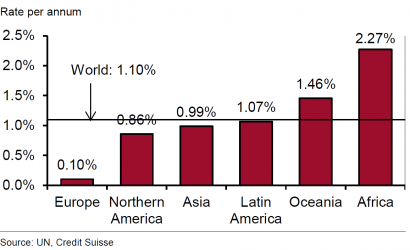

The population growth in Asia is now stable growing according to UN and Credit Suisse figures at a rate of 0.99% compared to the world average of 1.1% – while that of Africa which sits at 2.27% growth.

That said, as quality of life improves, the population of Asia, currently sitting at around 4.4 billion, will only shoot one way and while growth may be ‘stable’, as the population of Asia accounts for well over half of that of the world, a 1% growth rate remains monumental.

As stated in a study entitled The Future of Population in Asia by the East-West Center:

“During the second half of the 20th century, life expectancy increased by more than 20 years in all three of Asia’s sub-regions—from 43 to 71 years in East Asia, from 41 to 65 years in Southeast Asia, and from 39 to 62 years in South and Central Asia.”

This can largely be attributed to significant developments in public healthcare and modernisation processes imported from Europe and North America.

In Asia, economic growth and modernisation caused a drop in death rates comfortably before they had an effect on birth rates.

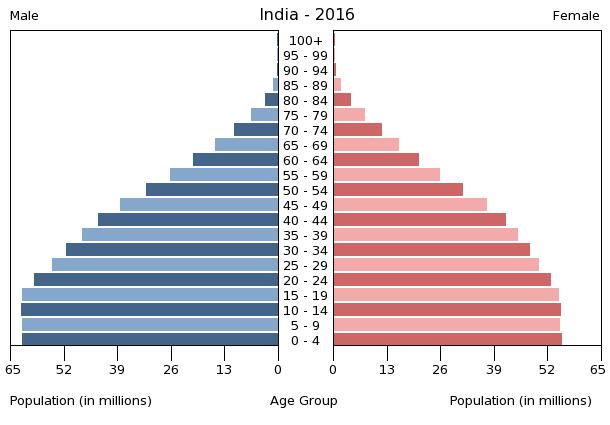

In essence, while population growth has slowed, it is still growing at an unsustainable rate with respect to feeding itself. Couple this with the fact that the Asian population is ageing as healthcare and overall quality of life improves; all of a sudden we have a continent bursting at its seams. While that of India as seen in the graphic below remains grossly young, as it begins to feel the effects of modernisation and healthcare improvements, this young generation too will live longer than any of its predecessors and subsequently require exponentially more food.

Source: CIA

It is expected that more than 60% of cereal demand in the developing world will come from South and East Asia by 2030, with cereal demand expected to increase 1.6% annually in South Asia and 1.2% in East Asia up until 2030 according to research by the Asian Development Bank. Food production efficiency however can’t keep up with this level of demand.

The very nature of demand is changing

Globalisation, urbanisation and rapid economic growth have had a significant impact on diets and lifestyles in South East Asia in particular, according to a study conducted by South East Asian Nutrition Surveys (SEANUTS) that looked in particular at Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam.

“While population growth has slowed, it is still growing at an unsustainable rate…”

In Asia and the Pacific, food security is being fundamentally altered – as patterns of food consumption and production change according to the drive for global food sustainability. These forces stem from the region’s huge population, changing demographics, and spectacular economic rise.

As standards of living improve, the populations of Malaysia, Thailand and in the urban centres of Vietnam and Indonesia can afford to spend a larger proportion of income on food to the point where conversely over-nutrition is becoming an issue – particularly in Malaysia and Thailand according to Food Industry Asia.

Furthermore, the very nature of food desired has fundamentally changed following mass urbanisation in the region. Asia’s urban population share almost doubled in 30 years from 24.6% in 1970 to 46.5% in 2010 – and it is expected to reach 70% by 2050 as detailed in statistics from the United Nations.

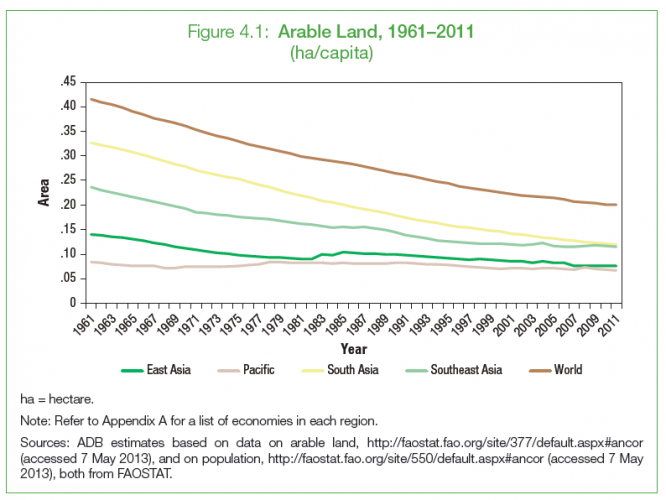

Urbanisation fundamentally destroys arable land spread and limits land resources, and Asia’s emergent ‘middle class’ from urbanisation has also radically shifted its diet away from staple carbohydrate intake such as in cheaply-produced cereals towards demand for meat, dairy products, fruits, and vegetables.

Source: Asian Development Bank

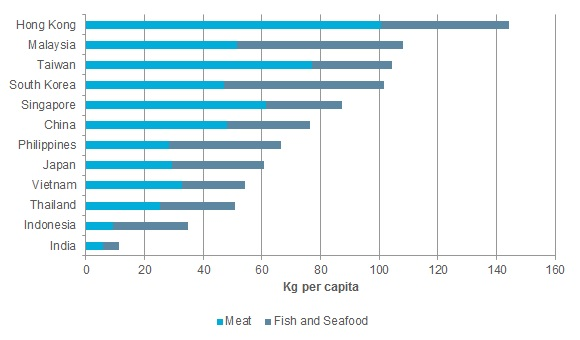

Meat consumption increase in particular puts a significant strain on resources. China, for example saw its meat consumption increase five-fold over the last 30 years, demanding a quarter of the total world supply in 2012. This incredible figure and their per capita consumption is generally indicative of regional demand as seen below in the graphic and puts an exceptional strain on resources and corresponding productivity growth as both grain production and water demand are put under increasing pressure. While Chinese pork demand is argued to be in decline due to several health scares and an emerging culture of anti-indulgence, the meat demand of India, an otherwise predominantly vegetarian nation with currently very low level of meat consumption per capita, is growing significantly.

Per capita meat, fish, and seafood consumption by market in 2014 (total volume)

Source: Euromonitor International

While regional productivity levels have been growing, the rate at which they are improving is itself is in steady decline and yield growth too is in trouble. While our in depth analysis of productivity levels will take place later in the series, in summary, the increasing amount of people to feed, while in decline in terms of growth rate, nevertheless demands more food and not just that, the food in demand itself demands higher resource-consumption – be it feeding the animals to then be slaughtered or the eating up of arable land due to urbanisation and population growth.

Boosting food production to meet ever-increasing demand inevitably arrives at the expense of already damaged natural resources. With growing pressures, enhancing agricultural productivity with higher yields might reconcile this issue but as we will later explore, this is easier said than done.

Urban consumption habits

Consumption habits of the new urban, what we might call ‘middle class’, population have drastically changed. The increasingly affluent Asian population demands more protein-rich and resource-demanding products and not just from an increased demand for meat and dairy products. Vegetables and sugars as well as new explicitly commercial goods from renowned ‘Western’ brands have risen in popularity. A large McDonald’s, KFC or Burger King becomes almost a consumer expectation in each city. These products require far more water and energy per calorie produced than cereals and the food consumption habits of say twenty years ago and thus are harder and more costly to mass-produce for the expanding demand.

Furthermore, many of the modern, working city professionals dine alone, require fast, easy-to-prepare products and often care about its nutritional content. All these factors require more packaging and energy consumption in their preparation as well as transportation costs.

Not only does a larger Asian population demand more food in terms of quantity, the quality and convenience of the food they expect also increases its drain on natural resources and energy to the point where the model of food sustainability is in real jeopardy.

It must be said that food security is not merely a question of quantity and many of the urban population do now enjoy a far more nutritious diet than before.

That said, despite increasing affluence in Asia, large segments of the population remain hungry, and indicators such as child and maternal under-nutrition show that the region is lagging in terms of achieving nutrition security.

In the next section, New Food will explore how distribution of affluence, poverty and climate change are all affecting and actively contributing to a worrying level of food insecurity in a region in which more than 60% of the world’s 1.2 billion people living on less than $1.25 a day inhabit and is also home to 537 million undernourished people – about 62% of the global total.

Sources

OECD, Food Security Challenges in Asia

Asian Development Bank, Food Security in Asia and the Pacific

The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2014, Feeding Asia-Pacific and Australia’s role in regional food security

China and Africa’s relationship should ensure African people are able to feed itself first. Africa is starving, the world is eating and using Africa’s resources. Africa must demand fair trade.