Pasta processing and nutrition

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Posted: 18 December 2008 | Carlo Cannella, Professor, Department of Medical Physiopathology – Food Science & Nutrition Unit, ‘La Sapienza’ University of Rome | No comments yet

Pasta has ancient roots that go back approximately 7,000 years to when humankind abandoned his nomadic lifestyle, started to cultivate the land and learned how to process grain. For many years, Marco Polo was credited with introducing pasta to Italy after his voyages in China, but several written documents deny this. In one of them, dated 1154, the Arab geographer Al-Idrin mentions ‘food made of strings’ called ‘triyah’ which was produced in Palermo. It is therefore thought that pasta, intended as ‘maccheroni’, actually originated in Sicily, around Trabia, near Palermo.

Pasta has ancient roots that go back approximately 7,000 years to when humankind abandoned his nomadic lifestyle, started to cultivate the land and learned how to process grain. For many years, Marco Polo was credited with introducing pasta to Italy after his voyages in China, but several written documents deny this. In one of them, dated 1154, the Arab geographer Al-Idrin mentions ‘food made of strings’ called ‘triyah’ which was produced in Palermo. It is therefore thought that pasta, intended as ‘maccheroni’, actually originated in Sicily, around Trabia, near Palermo.

Pasta has ancient roots that go back approximately 7,000 years to when humankind abandoned his nomadic lifestyle, started to cultivate the land and learned how to process grain. For many years, Marco Polo was credited with introducing pasta to Italy after his voyages in China, but several written documents deny this. In one of them, dated 1154, the Arab geographer Al-Idrin mentions ‘food made of strings’ called ‘triyah’ which was produced in Palermo. It is therefore thought that pasta, intended as ‘maccheroni’, actually originated in Sicily, around Trabia, near Palermo.

The production of pasta at an industrial level began in the late 700s around Naples, where the climate permitted the cultivation of grain and there were excellent conditions for drying the product in the sun. With the introduction of the process of drying by hot air, the production could finally spread to the rest of the country.

Pasta processing

Pasta is produced by mixing flour with water, then kneading the dough in different shapes and sizes which are dried out to allow preservation.

The organoleptic properties of pasta will mainly depend on the chemical composition of the semolina used during its processing and on the interaction between its main components (protein and starch) with the water added in the beginning for mixing and kneading and later for cooking. A high gluten content allows the product to remain ‘al dente’ (literally, ‘tooth style’) even after prolonged cooking.

Dried pasta is produced by starting with durum wheat (Triticum durum), while fresh pasta uses flour made from tender grain. The production process follows various stages:

- Selection of the grain, depending on hygienic, chemical and physical characteristics

- Crushing of the grains to obtain semolina

- Mixing and kneading: the flour is mixed with water – biologically pure and relatively soft – so that gluten forms, which creates a protein network able to capture the grains of hydrated starch. During the kneading process, the mixture becomes homogeneous and elastic

- Drawing out the mixture to form the various shapes that characterise the product

- Drying: pasta is placed in drying ovens; in fact, Italian law requires that pasta must not exceed 12.5 per cent humidity. Drying is the most delicate part of the procedure, where the pasta is repeatedly ventilated with hot air and the humidity produced is eliminated

- Cooling: the product is brought to room temperature

- Packing: pasta is wrapped by materials that will protect the product from humidity and external contamination

The higher the roughness acquired during the drawing phase, the greater the capacity of keeping the sauce. Pasta drawn in bronze draw-plates has a higher roughness, as well as a more opaque aspect, whereas pasta drawn in Teflon or steel draw-plates tends to have a higher shine and a smoother aspect.

Nutritional characteristics of pasta

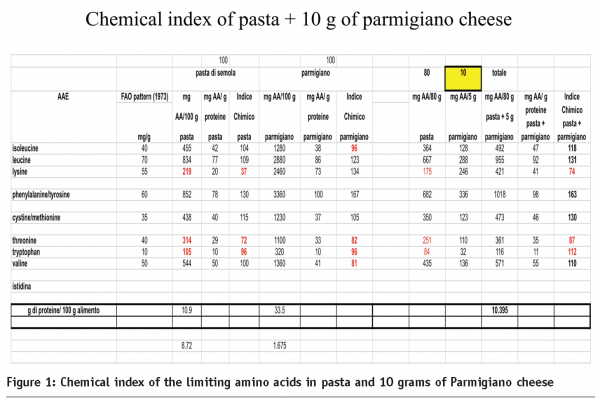

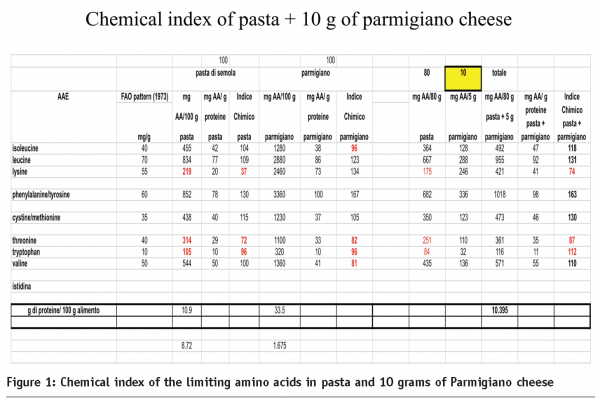

Pasta is a starch-rich food (79 per cent), with a moderate percentage (11 per cent) of protein with low biological value (chemical index = 56, due to its scarce percentage of lysine, tryptophan and threonine); this can be easily balanced by combining it with small quantities of meat, fish, eggs (in egg-made pasta), cheese (‘grana’) or legumes. For example, adding 10 grams of grated cheese (a little less than a tablespoon) can significantly improve the chemical index of the limiting amino acids: lysine goes from 37 to 74, threonine from 72 to 87, tryptophan from 96 to 112 (Figure 1). The combination with the egg in egg-made pasta and with 10 grams of ‘grana’ can improve the nutritional value even further.

In terms of vitamins and minerals, it contains a discreet quantity of niacin, very little vitamin B1 and B2, a high content of potassium and phosphorus, a reasonable amount of calcium and very little sodium.

Due to its low water percentage (10.8 per cent), dry pasta is an energy dense food, even though its fat percentage is negligible (1.4 per cent): its energy value is approximately 353 kcal/100 gram. The reference portion is 80 grams of dried pasta and 120 grams of fresh pasta (Wellbeing Index, WI, in a dietary regime of approximately 2000 kcal, www.piramideitaliana.it); a daily consumption of one WI of pasta is suggested, up to a maximum of eight WI a week (one pasta package of 500 grams can serve up to six portions).

In the past, pasta has often been blamed for causing obesity, diabetes and dislipidemiae and has therefore been removed or even banned from low-calorie diets or dietary regimes targeting subjects affected by metabolic imbalances. Based on scientific scrutiny, all the evidence is pointing to its total absolution, without adjournment to court! In fact, within a balanced dietary regime, pasta contributes to the glucidic amount, which should provide more than half (55-60 per cent) of the daily energy intake, allowing us to avoid an excessive intake of fat and protein. In addition to being the basic component of a balanced diet, carbohydrates are used by our body as its main source of energy. In particular, adult individuals need approximately 180 grams of glucose to fulfil their nervous system and red globules’ energy needs. Conversely, a diet too low in carbohydrates involves excessive proteins catabolism and ketone bodies accumulation. According to the Mediterranean dietary regime, which is recognised by the scientific community as the ideal model for a balanced and correct diet, a high consumption of fruits, vegetables and complex carbohydrates (as for starch in pasta) is related to health promotion and prevention of chronic-degenerative diseases.

A first distinction should be made between simple and complex carbohydrates: the former shouldn’t exceed 10 per cent of daily calories, are absorbed rapidly, promptly increasing glycaemia; the latter, such as starch in cereals and their products (as for pasta), in legumes and tubers, require a more complex digestive process.

Starches are large-molecular-weight alpha-linked polymers of glucose units arranged in either straight (amylose) or branched chains (amylopectine). They can only be found in plants, stored as energy reserves in the form of granules, made up of 70 per cent amorphous and 30 per cent crystalline regions.

Amylose is the straight-chain form of starch, based on several hundred glucose residues linked by alpha-glucosidic bonds between carbons one and four of adjacent glucose molecules. Amylopectin is the branched-chain component of starch, based on straight chains linked to side-branches by additional bonds between carbons one and six of two adjacent glucose molecules.

A variable percentage of starch, although in limited amount, can resist digestion and therefore be called resistant starch (RS). Together with dietary fibre, it enters the colon and is fermented by the colonic microflora with the production of by-products such as short chain fatty acids – SCFAs – (acetate, propionate and butyrate) – hydrogen and methane. SCFAs are rapidly absorbed and contribute to the host’s energy metabolism. SCFAs are of interest for their functional effects on human health: once absorbed by the colon’s mucosa, they can cover up to 10 per cent of daily energy needs of the host, while promoting calcium, magnesium and iron absorption, and stimulating proliferation and differentiation of epithelial cells of the intestine (trophic effect). ‘In vitro’ studies have also shown that propionate and butyrate can significantly suppress the growth of neoplastic cells.

As for the Glycaemic Index (GI: how quickly the body absorbs the sugars in food), pasta has a lower GI than rice, potatoes and bread, while the average GI for pasta is similar to that of legumes. ‘Al dente’ has a lower GI than overcooked pasta.

Benefits of adding vegetables to a pasta dish

Adding vegetables to a pasta dish, such as garlic, onions, tomatoes, carrots and basil (according to Mediterranean tradition), not only produces favourable effects on blood lipids but also protects our body against oxidative stress. Oxidative damage is thought to represent one of the mechanisms leading to chronic diseases such as atherosclerosis and cancer. Many studies suggest that there is a strong link between fruit and vegetable consumption and risk of death from cancer or coronary heart diseases. The preference for fresh produce in the Mediterranean diet will result in a higher consumption of raw foods, a lower production of cooking-related oxidants and a resulting decreased waste of nutritional and endogenous antioxidants.

Tomatoes can be added fresh or as tomato sauce. They are the main dietary source of lycopene, the carotenoid that gives them their red colour and has a very strong anti-oxidant activity. Lycopene has been linked to a decreased risk of prostate and breast cancer, and may exert a protective action against the damaging effects of ultraviolet radiations. Ripe tomatoes have a higher lycopene percentage. Due to its solubility in oil, its bioavailability is higher in tomato sauce cooked in olive oil.

Adding carrots means not only the addition of the sweet taste of this root, but also the orange carotene, which is a powerful phytochemical able to fight free-radical cellular damage in the body, possibly guarding against a wide range of chronic diseases. Alpha and beta-carotene can both be converted to vitamin A inside the body. Research has linked alpha-carotene to a reduced risk of lung cancer and to other protective functions such as cataracts, slowing the progression of heart diseases, and boosting the immune system.

The addition of onions cut into small pieces allows the release of quercetin. Quercetin is a type of plant-based phytochemical known as a flavonoid, also abundant in apples and other fruits and vegetables of the white colour group. Flavonoids, particularly abundant in onions and apples, are powerful antioxidants whose beneficial effects have been associated to the protection against tumours and to the optimal health of lungs. They have also shown antiviral and antibacterial properties. Quercetin remains intact and bio-available after cooking. Together with garlic, onions contain compounds called organosulfides, which are able to halt the production of nitrates into carcinogens, protect our organism from coronary diseases (they can lower cholesterol levels and blood pressure), increase blood fluidity and prevent blood clotting.

Olive oil is the starting ingredient for the sauce, first cutting and browning some onions by heating; this allows the solubilisation of the phytochemicals and the increase in their bio-availability. Olive oil is particularly rich in monounsaturated fatty acids – MUFAs (approximately 75 per cent) – which have been proven to lower LDL (bad) cholesterol level in the blood, but not HDL (good) cholesterol level (related to a lower risk of cardiovascular diseases). On the contrary, polyunsaturated fatty acids (abundant in corn oil, soybean oil, sunflower oil, sunflower oil, fish and seafood) can lower both LDL and HDL levels. Several studies confirm how a diet rich in MUFAs can also reduce cholesterol tendency to undergo oxidative damages. Oxidative stress can be considered the first step toward atherosclerosis (damage of arterial walls, plaque formation, fat deposit, hardening and restriction of arterial lumen), increasing the risk of heart problems and strokes. For the above mentioned reasons, olive oil can be considered the ideal choice of fat for the health of the cardiovascular system. Besides being rich in MUFAs, olive oil owes its health properties to the abundance in protective compounds – phytochemicals – particularly polyphenols (which confer its unique colour to the product), and to vitamin E. Vitamin E is a powerful antioxidant, able to neutralise the formation of free radicals (unstable compounds which can damage cell membranes, therefore increasing the risk for chronic-degenerative diseases). It can also help to further prevent LDL from oxidising.

Conclusions

Due to its incredible versatility, pasta can be used for the preparation of endless recipes. With its ample regional diversification, Italian gastronomy can offer a countless choice of combinations with legumes, meat, fish or cheese (tortellini, lasagne, agnolotti, etc.). Daily consumption of this renowned Italian food, which is a fundamental element of the Mediterranean tradition, can protect our body from obesity and metabolic diseases, as long as the right quantities are respected (one portion is equal to 80 grams of dry product), and there is no overindulgence in sauces too rich in fat. Pasta can therefore be part of a balanced and healthy diet plan and satisfy the fundamental hedonistic role of nutrition.