Chocolate mass – an overview on current and alternative processing technologies

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Posted: 27 October 2014 | Siegfried Bolenz | 4 comments

A lot of time has passed since the first refiner conches were built to make chocolate. At that stage all necessary processing steps were done in the same machine, which sometimes took a week to get the final product. This paper is not intended to summarise all the technical developments since then as such information is available in textbooks1. Instead it aims to briefly introduce the different systems for chocolate mass production offered by various companies in order to give readers an overview on what is currently available on the market.

Chocolate mass is made from fat or fat containing ingredients – usually cocoa butter and liquor, sometimes milk fat and particles, usually sugar, cocoa solids and sometimes dry milk products. Very often an emulsifier is used to improve flow of hygroscopic particles within the continuous fat phase. During production several incidents occur:

- Reduction of large particle sizes by grinding

- Covering each individual particle by fat/emulsifier to reduce particle interaction during flow

- Removal of water contained in raw materials, as it would form undesired sticky layers on hygroscopic particles

- Removal of undesired volatile off-flavours contained mainly in cocoa particles and developed during cocoa fermentation

- Flavour development

The two latter points could also be combined as they are difficult to distinguish.

Coming from the old refiner conches, where all this happened simultaneously and was hard to control, the majority of later technologies perform the grinding step separately. Only few mill types are able to handle chocolate preparations, as it is initially a very sticky mass, which can transform to a sticky powder during milling, when specific surface of particles increases. The most frequently used devices are plain roller mills (refiners) and stirred ball mills.

Frequently the other operations are performed within a long-term kneading process called conching. Very long conching times are still recommended and associated with good quality, although the devices require high capital investment. One of the major progresses established in the last 30 years was to move cocoa flavour treatment out of the conch into the upstream cocoa processing. Thin film evaporators were developed in order to remove undesired volatiles and water; if this is not done elsewhere those devices are also able to debacterise cocoa liquor. Unfortunately the very popular Petzomat is not built any more, but alternatives from other companies are available. Nowadays chocolate producers can strongly reduce conching times if they insist on using pre-treated cocoa liquor of high flavour quality. Untreated cocoa is also still used, which then requires extra conching, like in former times.

Similar principles are followed for milk chocolates by developing milk powder pre-treatment procedures. For example it was proposed to dry skimmed milk powder to below one per cent water and to coat it with fat, which allows us to perform a very short liquefaction process instead of classical conching2.

Crumb is an ingredient made by drying milk together with sugar and cocoa liquor. Originally this was done for preservation of the milk, but nowadays it is performed in order to create the strong caramel flavour preferred in some countries. For downstream mass production the same technologies can be used, as with other chocolate types.

If cocoa butter is replaced by another fat, the product is usually called compound and not chocolate. Technologically most compounds are close to chocolate mass and similar equipment can be used to make it. The largest difference is rather an economical one, as very expensive cocoa butter is replaced by relatively inexpensive alternative fats.

After some initial information on chocolate mass properties the systems available on the market will be introduced. For that purpose information was obtained from various manufacturers, followed by questions and discussions on aspects such as:

- Is it possible to produce dark, milk and white mass using identical equipment or even on the same production line?

- What are the main advantages of the process for larger and also for smaller chocolate producers and what is the minimum size of an industrial production line?

- How much energy does the process require?

- What is the approximate capital investment necessary for a production line?

Of course not all questions could be answered. In particular the last point, as process equipment is usually designed individually by machine manufacturers for their clients. So in practice, chocolate makers will always have to negotiate individually with suppliers. This paper will provide an introduction to the possibilities on the market.

Chocolate mass properties

Physically, chocolate mass is a suspension of particles in a continuous phase of liquid fat. Downstream when producing final products for the consumer, fat crystallisation is initiated and the mass is forced into the desired shape and solidifies. These steps are not considered here, although many properties of the final product can be predicted by measurable properties of the still liquid chocolate mass. Therefore flow properties are usually measured at a temperature of 40°C, which is close to the temperature that chocolate melts in our mouths. So texture sensations like a smooth melt or a sticky behaviour are usually correlated to flow properties.

As chocolate mass is a non-Newtonian fluid we have to measure its shear stress at different shear rates, which results in a flow curve. Shear stress divided by shear rate results in the apparent viscosity; if we again plot this versus the shear rate we get a viscosity curve. Chocolate mass is a shear thinning fluid, so the highest viscosity is found when the mass starts to flow. Interaction between particles is considered to be responsible for this behaviour3, which is very different to Newtonian fluids such as water. So one important part of the flow curve is at very low shear. The yield value defines the shear stress, when the mass starts to move. As a minimum shear rate is necessary for the measurement, usually the yield value has to be extrapolated from the flow curve according to model equations, like the ones developed by Casson and Windhab1. Yield values or measurements at low shear stress also have a great practical importance, as many industrial operations are carried out with masses flowing slowly, for example the equal distribution of still liquid mass in a mould.

On the other hand side some processing is done under high shear, e.g. when pumping or spraying masses. This is best described by the other end of the flow curve. So usually it is extrapolated to infinite shear, the result is then called Casson or Windhab infinite viscosity. Naturally, fat content, emulsifiers and ingredient properties have the largest influence on viscosity. After those, particle size distribution and particle package density are also important. Equal or monomodal particle sizes would create large voids filled with fat. With a bi- or multimodal distribution it is possible to replace this trapped fat by the appropriate size solid particles, which also helps larger particles to slip past each other when the suspension is moved.

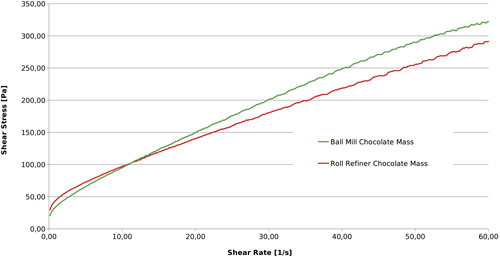

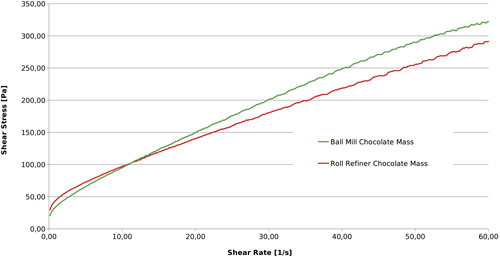

Figure 1

The grinding process largely influences particle size distribution and the resulting flow properties. Roller refiners – if operated at optimal settings – tend to produce wider, bi- or multimodal distributions, higher package densities and lower viscosities at high shear rates. In contrast, ball mills result in narrower distributions, less specific surface and lower yield values4. An example is shown in Figure 1.

Physically measurable properties of chocolate masses, like flow attributes or hardness, are correlated to sensory perceptions such as snap, hardness, melting and the like. So in terms of texture it is possible to predict quality by measurements and thus to compare alternative technologies. This is much more difficult in terms of flavour. Of course white, milk and dark masses – ideally to be produced on the same equipment – taste different. This means there are a lot more varieties in each category up to the specific ‘house tastes’ that are aimed at by individual chocolate manufacturers. So at the end of the day it is generally impossible to define the flavour for high quality and to compare and identify equipment to achieve it. If considering processing alternatives it will always be necessary to adapt recipes and technology to each other in order to get the desired result.

Roller refining and conching

This technology is used by the majority of chocolate producers in Europe. A typical line consists of mixer, 2-roll-refiner, 5-roll-refiner and conch. In the mixer the largest part of the recipe is blended, although some fat is left out, as otherwise the mix would be too fluid for the refiners. The 2-roll-refiner crushes sugar crystals to sizes below 100µm. Alternatively, sugar can be ground separately by a sugar mill, which was common practice some decades ago. Although sometimes this set-up can still be found, most companies nowadays prefer the 2-roll-refiner due to the danger of dust explosions in sugar mills. The following 5-roll-refiner is a sophisticated machine, not very easy to operate, but essential for final product quality. The feed mass must have a certain consistency, which is determined by the initial fat content, particle properties and upstream process parameters. Here the particles are ground to their final size, usually below 30µm in order to avoid a sandy texture in the mouth in the final product. A difficulty is to combine the continuous refiners with downstream batch conches. Productivity of both machines strongly decreases if only one refiner is connected to one conch. Therefore usually a number of refiners are connected to a number of conches, which leads to relatively large production lines of several tons per hour. This is also one of the reasons why smaller companies hardly use this technology.

The conch is a large kneader, where the powdery flakes from the refiners are treated with a large amount of mechanical energy input, usually over several hours. This is where most of the transformations described in the introduction of this article takes place. During the process the remaining fat and emulsifier are added. Conches are built in various forms and can be equipped with one, two or three mixing shafts. More detailed descriptions of the process can be found in1.

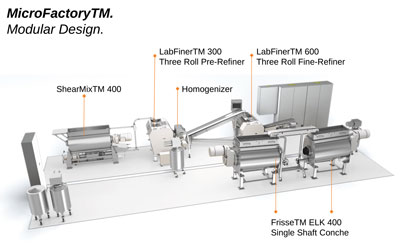

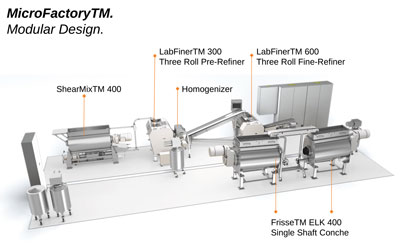

Figure 2

The Swiss company Bühler is market leader in this technology and looks back to a long experience in building and installing complete production lines8. In order to also meet the needs of smaller producers, recently the MicroFactory™ line was launched with a capacity of 300-600 kg/h, where the 2+5-roll-refiners are replaced by two three-rollers, see Figure 2.

Figure 3

Since the Dutch company DuyvisWiener joined with F.B.Lehmann and Thouet, they are also in a position to supply complete lines consisting of refiners and Thouet-conches. Interesting for smaller companies is the F.B.Lehmann 5-roll-refiner with integrated ‘micro’-2-roller9. Nevertheless also here one refiner would need several hours to fill a large 6-t-conch, which can only be solved by always having one machine idle or by using at least two smaller conches. For very small scale or test production the company also builds a pilot scale 5RR with 50cm rolls and 3-rollers.

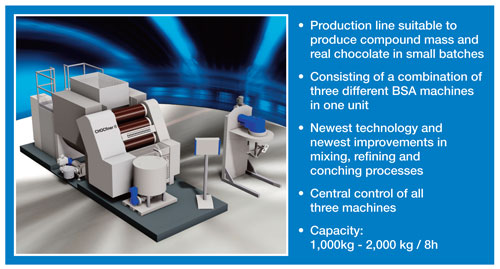

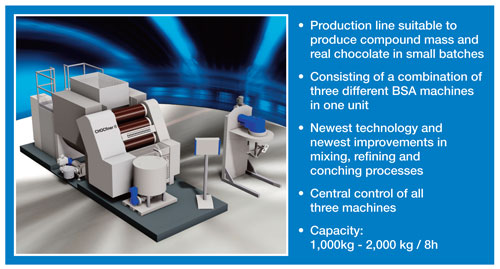

Another solution for smaller companies or for niche products is offered by BSA-Schneider, an established conch builder, who since recently also builds refiners. Their CHOCompact system combines a small 5-roll-refiner with a conch10 (see Figure 3). Only one machine is operating at the time, so the conch has to wait for the refiner and vice versa. There are several other companies building refiners, e.g. Carle&Montanari-OPM11, HDM-Petzholdt-Heidenauer12 and conches such as Thouet13 and Lipp Mischtechnik14.

Continuous conching

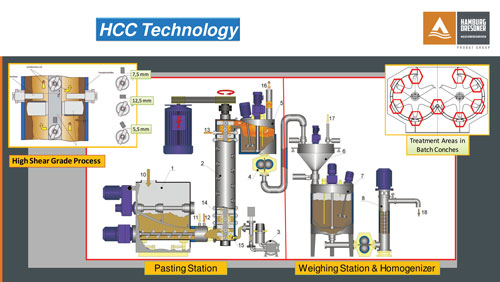

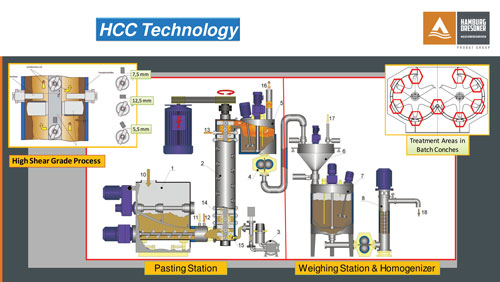

Petzholdt-Heidenauer, now part of the Probat group, carries forward the long experience on continuous conching dating back to the 1970s. The solution currently offered is based on using conventional 5-roll-refiners. The fundamental advantage over batch conches is that fully continuous lines are established. On the other hand side a minimum throughput of 1,250kg/h is required over a longer time, so the process is not suitable for frequent recipe change or smaller companies.

Figure 4

The process is shown in Figure 4. Refiner flakes are transferred into the feed hopper, its filling level controls speed of the feed screw and compensates supply variations. While some cocoa butter is added, the screw feeds the pasting columns. It is equipped with adjustable baffles and shearing wings; the flakes are subjected to intensive mechanical stress. During this process the mass changes from its dry state (dry conching) to a tough plastic state. Cleaned conditioned air is supplied by fan. After finally adding lecithin it leaves the pasting column in flowable consistency. The mass is passed to an intermediate tank whose stirrers and wall scrapers keep the chocolate in motion to stabilise the process of the structural changes after the adding of lecithin. Process air, loaded with volatile and undesired flavour is separated. In the weighing station the recipe is completed by liquid components. The wall scraper of the vessel prepares already a pre-mixture. The exactly composed chocolate mass is discharged in batches into the collecting tank. There it is further mixed and cooled. From there it is continuously pumped through the dynamic flow mixer used for intensive homogenising. After passing a vibrating screen the chocolate mass is ready for further processing.

According to Petzholdt-Heidenauer, advantages are:

- Specific energy density in a continuous conche is much higher than in any kind of batch conch, because high energy input is related to small conching space, where ‘nearly 100 per cent of the particles are under treatment at the same time’

- High efficiency rate of the energy employed to effect the structural changes

- High specific surface of the processed chocolate mass as a precondition for intensive exchange reactions with the supplied ambient air

- High degree of precise and equal mechanical stress on all particles of the chocolate.

The device holds 450 to 500kg, which results in residence times of 15-20 minutes in the conch and 4-5 minutes in the column. Energy density is up to 1200 kW/t and energy input 70 to 90 kWh/t. The modular structure allows us to extend the plant step by step.

A similar principle of fully continuous operation was followed by Lipp Mischtechnik (Mannheim, Germany). Here the focus lies on removing undesired water from the raw materials before liquefaction and not during that step. This is possible through pre-drying refiner flakes5 or milk powder6. Downstream, the liquefaction can be done in a very rapid batch process or continuously using a high-speed in-line mixer14.

Macintyre system

This very unique machine resurrects the traditional method of conching and grinding at the same time, as we know it from the Lindt longitudinal conch1. It consists of a double-jacket cylinder with serrated internal surface. Spring-loaded scrapers break the particles during rotation; volatile water and flavours are removed by ventilation and heating.

There has been some discussion about the optimisation of flow properties and flavour in those machines and it has also been tried to combine it with other systems, e.g. refiners1. It is also known, that operation is relatively noisy. An advantage is that batch sizes between 45kg and 5t are possible, which means a lot of flexibility for smaller companies.

Ball milling

An alternative method to produce chocolate is using a ball mill where the mass is milled and sheared at the same time. Although cocoa liquor is usually ground by ball mills, those are not popular for chocolate mass in the European industry. Nevertheless those systems are commonly used worldwide. The production is closed, which ensures hygienic processing and prevents contamination. Industrial-scale ball mills work continuously. Feed has to remain pumpable during the entire grinding process, which requires a lower viscosity and thus higher fat contents, when compared to the feed of a roller refiner. Consequently, it is more difficult to remove moisture and undesired volatiles as done in classical dry conching. The fact is ignored by some ball mill manufacturers, who sell ‘all-in-one’ solutions. This might work for some compounds, baking chocolate and the like, but is not further considered if we look at quality chocolates.

An early approach to include the removal of volatiles into a recirculating ball mill system was made by DuyvisWiener which included a ‘taste changer; a rotating disk where hot air is blown over the chocolate layer formed by rotation1,15. These devices are still sold for small scale applications. F.B.Lehmann, now part of DuyvisWiener, has a long experience in building thin film evaporators and horizontal ball mills for cocoa processing and had also offered systems for chocolate mass production. This is continued after the merger and further processing alternatives have been designed using devices from both subsidiaries. So for larger continuous lines, thin film flavour treatment can be combined either with horizontal or vertical ball mills15. Together with the traditional refining conching solutions (see above) the company now can offer a large variety of processing alternatives to their clients.

Figure 5

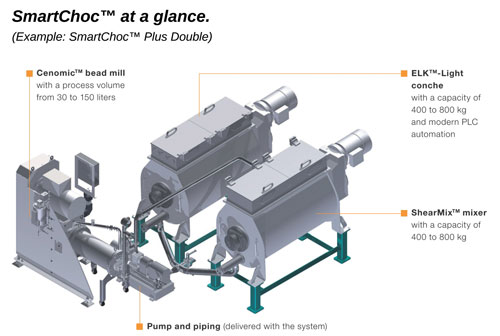

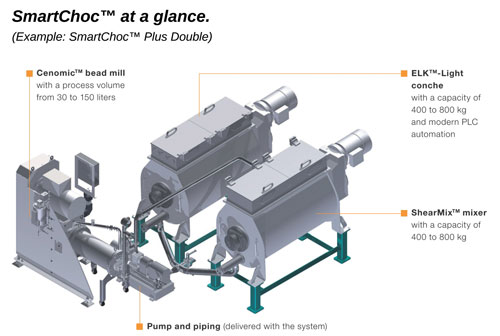

Recently, Bühler seems to have followed a similar strategy. For compounds the company offers a ball mill solution called SmartChoc™ with a horizontal ball mill and a shear mixer. After adding a single-shaft conch for flavour treatment (light conching) the system for small scale production (60-300g/h) is now called SmartChoc™ Plus and allows manufacturing a variety of chocolate and compound masses16 (Figure 5).

Another system is offered by Netzsch17; it comes in variations for smaller companies (batch size 25-300 kg/h, called ChocoEasy) and also for larger production (batch size 750-6000kg, then called Rumba). After pre-grinding sugar by an impact mill the raw materials are mixed in a conch, where hot air is applied for flavour treatment during dry conching. After that the mass is liquefied by adding cocoa butter and then ground by circulation through a horizontal ball mill. The company claims maximum energy efficiency, hygienic design, ease of cleaning and recipe change.

Figure 6

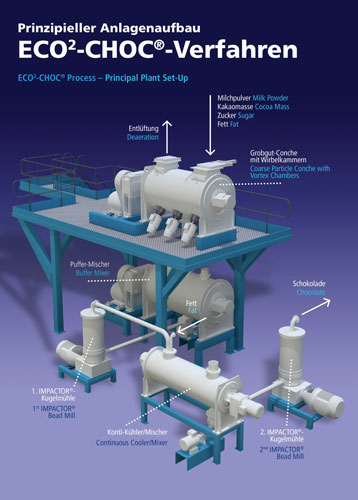

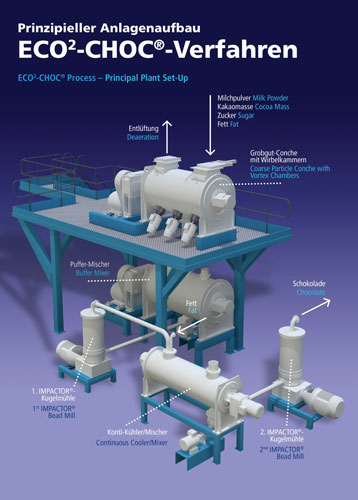

After building highly reputed conches, batch and in-line mixers for a long time, Lipp Mischtechnik has now developed a complete chocolate line called Eco2choc® (Figure 6). It is based on the ‘coarse conching’ processing concept. Development and optimisation are described in7; research has also shown that milk chocolate of good flow properties and taste can be produced. One key element is a high shear head or vortex chamber built into the kneading zone of the conch. It intensifies mass and energy transfer, but also reduces particle size of crystal sugar to approximately 300μm – thus no pre-grinding device is necessary. Coarse conching time can be short if just drying is needed, e.g. for white chocolate or milk chocolate with small quantities or high quality cocoa mass. If a stronger treatment is necessary, e.g. for flavour development of dark chocolate, this can be achieved by increasing energy input and time. The dry and pasty conching is generally done at low fat contents in order to improve volatilisation. Fat and other ingredients are added then and grinding can be performed from a buffer mixer by two vertical ball mills with an intermediate cooler. The latter helps to keep temperature of sensitive products below the desired level, e.g. when recipes contain lactose and glass transition during milling must be avoided. The process can be downsized for small production scale, then it consists of a conch with vortex chamber, a ball mill and a pump for circulation.

Discussion

One of the first things a chocolate producer has to consider are the influences of recipe, ingredients and particles on chocolate mass properties as discussed above. First of all, if raw material cost is less important, e.g. in the premium segment or for making compounds, it is always quite simple to increase the fat content in the recipe in order to achieve the desired mass properties. Also the taste can be largely influenced by choosing the right ingredients. In those cases, processing technology becomes less important and most of the systems on the market will be able to produce the desired quality.

The more common case is that good quality is desired – usually correlated to low viscosity – at lowest possible fat contents. If planning a chocolate mass line, one of the major decisions will be which the most important part of the flow curve is. If low shear downstream applications like moulding are in the focus, low yield values are important; here ball milling could be an advantage. On contrary, if the mass has to move fast, for example, if pumped or sprayed infinite viscosity is more important and roller refiners might be preferential.

Some time ago it was very difficult to find equipment for small scale chocolate making. This has changed; now there are a number of ball mill-based systems on the market and also smaller scale roll refiners have been developed. Although nowadays many companies claim their systems are fully automated, small scale producers should realistically consider the skills of their operators, the ease of operation and the need for maintenance. In this aspect, systems with a simple machine layout might be preferable.

For medium- and large-scale producers there are a wide range of technical options. The varying needs of chocolate producers and the various advantages and disadvantages of the systems on the market make it impossible to give a general recommendation. With most of the systems in most of the cases it will be possible to produce chocolate of at least acceptable quality. Fine-tuning and final choice has to be made in every single case; it is always both recipe and process that influences final quality and there is no ‘out-of-the-box’ solution. So the best possible advice might be:

- Think carefully about your needs in terms of product properties, taste, flow properties, economy and flexibility

- Then pre-select a number of possible systems/suppliers

- Then run enough tests on their machines with your own recipe in order to make a qualified final decision.

References

- Beckett ST (2009) Industrial chocolate manufacture and use. Wiley, Chichester

- Bolenz S, Kutschke E, Lipp E (2008) Using extra dry milk ingredients for accelerated conching of milk chocolate. Eur Food Res Technol 227: 1677–1685

- Windhab EJ (1995) Rheology in food processing. (Chapter 5 in Physico-chemical Aspects of Food Processing ISBN 0751402400). Chapman & Hall, London, pp 80–115

- Bolenz S, Manske A (2013) Impact of fat content during grinding on particle size distribution and flow properties of milk chocolate. Eur Food Res Technol 236: 863–872

- Bolenz S, Kutschke E, Lipp E, Senkpiehl A (2007) Pre-dried Refiner Flakes Allow Very Short or Even Continuous Conching of Milk Chocolate, Eur Food Res Technol 226:153–160

- Bolenz S, Kutschke E, Lipp E (2008) Using extra dry milk ingredients for accelerated conching of milk chocolate. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 227: 1677-1685

- Bolenz S, Manske A, Langer M (2014): Improvement of process parameters and evaluation of milk chocolates made by the new coarse conching process , Eur Food Res Technol 238: 863–874

- buhlergroup.com/europe/en/industry-solutions/processed-food/chocolate/chocolate-mass.htm

- fblehmann.com/chocolate-processing/refining/5-roll-refiner

- chocompact.com/

- cm-opm.com/en/applications/cocoa-chocolate/a4_1

- petzholdt-heidenauer.de/chocolate.htm

- thouet.com/chocolate-processing

- lippmischtechnik.de/en/produkte/conchier-maschinen/

- duyviswiener.com/chocolate-processing

- buhlergroup.com/europe/en/about-buehler/events/interpack-2014/interpack-2014-exhibits-at-a-glance.htm

- netzsch-grinding.com/en/confectionery-division/home.html

About the author

Prof. Dr. Siegfried Bolenz studied food engineering in Stuttgart-Hohenheim and started his career 1989 in a fruit juice company while studying for his PhD. From 1992-1997 he worked with Kraft-Jacobs-Suchard (now Mondeléz) in R&D on various dairy, food and chocolate process development projects. Since 1997 he has been professor of food technology at the Neubrandenburg University of Applied Sciences, where he teaches dairy, confectionery and beverage technology, product and process development. One research focus is chocolate processing, where he cooperates with various companies and has published a number of papers and patents. For further information visit: www.hs-nb.de/ppages/bolenz-siegfried.

Thanks for the comprehensive article on Chocolate making. I found it a very interesting read. If one was looking for a flexible system that can make a variety of chocolates using different fats which needs different change overs but still produces acceptable product quality, which technology would you consider? Has triple stone mill ever been considered for particle size reduction like they do for Cocoa Liquor?

Thank you … I am very satisfied

I am trying to access the article but it is not working

Hi Pedro, please accept my apologies, if you try again you should be able to access the article.