Can a vegan diet provide enough nutritional support for a pregnancy?

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Posted: 21 March 2017 | Leah Smith & Julie Abayomi | Liverpool John Moores University | 8 comments

Can a vegan diet provide adequate nutritional intake for a healthy pregnancy? We asked academics at Liverpool John Moores University to explore…

New Food vehemently believes that in order to drive progress forward in the food and beverage industry we must work with academia and science. Subsequently, we asked Dr Julie Abayomi of Liverpool John Moores University to work in collaboration with her student Leah Smith to discuss whether a vegan diet can support a healthy pregnancy…

Can women following vegan diets obtain their recommended nutritional intake during pregnancy?

Good nutrition in pregnancy is essential to avoid nutritional deficiencies in both the mother and the developing foetus. A mother’s diet during pregnancy will affect her child’s health for many years. So ensuring that women who choose a vegan lifestyle meet their nutritional requirements during pregnancy is of vital importance. The UK Vegan Society estimate that Vegan diets have increased in popularity by 360% over the last decade, with at least 542,000 people in the UK claiming to be vegan, avoiding consumption of all animal products1.

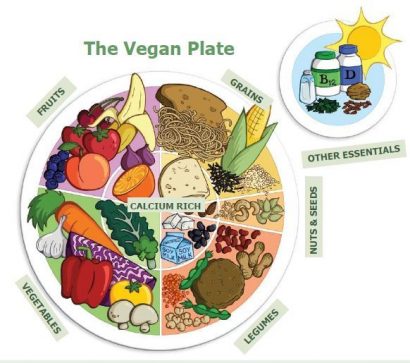

The Vegan Society recommends ‘an increase in vitamins and minerals’ but they go on to state ‘due to the body’s physiological response to pregnancy, nutrient absorption is often already increased’2. The British Dietetic Association (BDA) offers more cautious advice, stating that ‘well-planned and balanced plant-based vegan diets can support all healthy lifestyles, including healthy pregnancy preparation’3. A balanced diet occurs when the nutrients in food, balance with a persons’ particular needs4. Vegans often follow ‘The Vegan Plate’ (see figure 1), which is a reliable read-reference for a well-planned and balanced diet, shown on The Vegan Society website. Health benefits are often reported following adaptation to a vegan diet resulting in meals lower in saturated fat and higher in dietary fibre5.

Figure 1: ‘The Vegan Plate’ by registered dietitians Brenda Davis & Vesanto Melina.

(The Vegan Society, 2017)

Vegan diets often focus on high intakes of cereals, nuts, pulses, fruit and vegetables. These provide essential nutrients such as carbohydrates, dietary fibre, omega-3 fatty acids, carotenoids, folic acid, magnesium and vitamins C and E. However, the vegan diet is often comparatively low in macronutrients (protein and saturated fat) and other necessary micronutrients such as iron and zinc6. Many pregnant women following a vegan diet may be unaware of the potential deficiencies, believing that their lifestyle is a healthy option and so may not include all the recommended essential plant foods in their diet.

At risk nutrients

A vegan diet has potential to lack essential micronutrients. Confusion or reduced awareness of implementing important dietary changes during pregnancy may cause deficiencies and health implications for mother and baby. Including low birth weight (linked with iron deficiency), cretinism (due to iodine deficiency), preterm birth (zinc deficiency) or neural tube defects (folic acid deficiency) 7. At risk micronutrients include, iron, calcium, vitamin B12, iodine, zinc, omega 3 fatty acids, folic acid and vitamin D as good sources of these are mainly found in animal foods.

Iron

If pregnant women have sufficient stores of iron and normally meet the Recommended Nutritional Intake (RNI) for iron (14.8mg/day), then there is no increased requirement for iron compared to non-pregnant women. This is thought to be due to amenorrhoea, increased intestinal absorption of iron and the mobilisation of maternal stores during pregnancy8. Pregnant women should only take iron supplements on prescription if they have low serum ferritin (iron stores – usually tested halfway through pregnancy). Excess iron can result in constipation or hypertension.

Iron intakes may be reduced in vegan diets due to lack of haem sources in the diet, derived from haemoglobin and myoglobin in animal foods. Vegans may struggle to maintain optimal iron levels as non-haem iron (from plant sources) is less easily absorbed than haem sources9; this includes wholemeal bread, green leafy vegetables, nuts, pulses, beans, dried fruit and iron-fortified flour and cereals10. To allow comparison, the iron content of rump steak is 2.7mg/100g, whereas a plant-based non-haem source such as spinach, contains 1.9mg/100g. Iron from spinach is not well absorbed due to the presence of oxalates; these are derived from oxalic acid and impair iron and calcium absorption in food11. Furthermore, it is much easier to eat 100g of steak compared to 100g of spinach (see figure 2).

Figure 2: The iron content of a haem and non-haem source of iron and the amount of spinach required in order to achieve similar iron content to a portion of rump steak.

|

Food Source |

Iron Content (mg/100g) |

Iron Content per Portion |

Amount needed (g) to achieve similar iron content per portion of rump steak |

|

Rump Steak |

2.7mg/100g |

6.08mg/225g |

6.08mg/225g (One x 225g portion) |

|

Spinach |

1.9mg/100g |

1.52mg/80g |

6.08mg/320g (Four x 80g portions) |

Enhancers and inhibiters highly affect the absorption of non-haem iron, for example inhibitors such as coffee, tannins in tea, phosphates, and inorganic elements; calcium, magnesium and oxalic acid can all reduce absorption. However, enhancers such as organic acids; ascorbic acid (vitamin C), citric, lactic, malic, and tartaric acid, fructose, and amino acids; cysteine, histidine and lysine will increase iron absorption. Therefore, consumption of non-haem iron with a source of vitamin C (fruit or salad vegetables for example) will boost iron absorption8.

Sufficient plant-based dietary sources of iron are essential during pregnancy, otherwise iron deficiency anaemia can occur. As well as suffering from fatigue, dizziness, lack of concentration, pale skin and insomnia, iron deficiency anaemia during pregnancy is also associated with poor pregnancy outcomes such as low infant birth weight and height, reduced iron stores and preterm deliveries4.

Calcium

No evidence suggests that an increment in dietary calcium is necessary during pregnancy, due to mobilisation of maternal calcium stores. The RNI for adult women is 700mg and 800-1000mg for adolescents. During lactation, requirements increase to 1250mg for adults and 1350mg for adolescents8.

Calcium is predominately found in dairy products such as cow or goat milk, yogurt and cheese; all avoided in a vegan diet. Fortunately some plant foods such as soya, green leafy vegetables (excluding spinach), dried fruit, nuts, seeds, fortified bread and dairy alternatives such as fortified soya milk, are also good sources12. A well planned vegan diet will enable RNI to be achieved, although consideration of calcium absorption is vital. For example, spinach contains high levels of oxalate, a substance which hinders the absorption of calcium. Therefore, consuming low-oxalate green leafy vegetables such as cabbage, kale and rocket is essential to ensure a sufficient intake of calcium. Reducing consumption of salt and caffeine is recommended as they act as calcium inhibitors, decreasing absorption; whereas adequate protein intake (approximately 1g of protein per 1kg of healthy body weight) act as calcium enhancers, increasing absorption12.

Calcium requirements of pregnant adolescents are of particular concern; the RNI is higher than adult RNI as bones are still developing and building peak bone bass. Care must be taken to ensure sufficient and regular intake of plant sources of calcium for adolescents following a vegan diet8.

Vitamin B12 – Cobalamin

Maternal B12 deficiency can result in negative outcomes for both mother and baby such as increased risk of pre-eclampsia, pre-term birth, intra-uterine growth retardation and low birth weight. Recent studies have established an association between neural tube defects and inadequate vitamin B12 status13. There is increased risk of B12 deficiency if the pregnant mother is a long-term vegan who avoids fortified foods or follows a macrobiotic or raw food diet14. The RNI of 1.5 mcg/d is thought to be sufficient to prevent or treat critical side effects of vitamin B12 deficiency, including megaloblastic anaemia. There is no increment during (non-vegan) pregnancy assuming that an individual’s body stores would not be depleted in the outset of pregnancy8.

Reliable vegan sources of vitamin B12 are limited; foods fortified with B12 are useful, such as some breakfast cereals, soya products, nutritional yeast and some plant milks. Many vegans consume high enough levels of B12 to avoid damage to the nervous system and developing anaemia, but unfortunately may not get enough to reduce potential risks of developing pregnancy complications or heart disease14. Biological testing is often recommended to assess the B12 status of vegan women, to establish if B12 supplementation is necessary especially if intakes are low due to limited dietary sources15. B12 supplements providing 10mcg daily or 2000mcg weekly are recommended and vegans should ensure substantial intakes of B12 from fortified foods to increase optimal health during pregnancy. In the absence of supplements, the Vegan Society (2017) suggests consumption of fortified foods 2-3 times daily to provide at least 3mcg/day of B1214. It is often debated that widespread fortification of folic acid (in flour for example), may exacerbate the clinical and biochemical status of B12 deficiency, so any future food fortification policies are recommended to consider fortification of vitamin B12 too16.

Iodine

To prevent iodine deficiency, adult RNI is 140mcg with no increased increment during pregnancy8. The BDA states that adult intake should definitely not exceed 600mcg/d18. To ensure sufficient amount of iodine in a vegan diet, supplements are the most reliable source, for example VEG1, which contains 150mcg/tablet, as plant sources are not reliable17. Vegan women of child-bearing age should take a 150mcg iodine supplement daily, as a study highlighted that vegans’ urinary concentrations can be significantly lower than non-vegans19. This is because fish, milk and dairy products are the richest sources of UK dietary iodine. Vegetables can contain iodine although this is unreliable as it depends on the iodine content soil. Sea vegetables such as seaweed contain excess iodine and can be contaminated with toxins, therefore consumption more than once a week is not advised, especially during pregnancy4.

Insufficient or surplus iodine can result in thyroid problems, affecting how the body uses food for energy17. Mild iodine deficiency during pregnancy can have disastrous consequences, affecting the baby’s brain development and the child’s learning ability in later years, with reading difficulties and a lower IQ reported18. Extreme deficiency may result in cretinism; the foetus cannot produce enough thyroxin and foetal growth and brain development are severely retarded. Hypothyroidism, low activity of the thyroid gland, often results in the foetus perishing in the womb or causing death within the first week of birth20.

Zinc

The RNI for zinc in women of child-bearing age is 7.0 mg/day; it is suggested that metabolic adaptations in healthy women guarantee an adequate transfer of zinc to the foetus and therefore no increment is required8. However, vegan women will need to make a conscious effort to increase zinc intakes as plant sources are often high in phytates, which can block zinc absorption, especially unrefined grains; pasta, rice and wholemeal bread21. Dietary recommendations can be met by integrating rich plant sources of zinc such as wheat germ, sesame seeds, tofu, wheat bran, legumes, nuts and some fortified breakfast cereals22. To obtain sufficient zinc from plant sources, frequent consumption of large quantities will be required (demonstrated below):

Figure 3: Table demonstrating the zinc content of sesame seeds and the amounts required to reach the RNI of 7.0 mg/day.

|

Food Source |

Zinc Content (mg/100g) |

Zinc Content per 1 tbsp (9g) Portion Size |

Amount of Sesame Seeds required to Reach the RNI of 7.0 mg/day |

Number of Portions needed to reach the RNI of 7 mg/day |

|

Sesame Seeds |

5.3mg/100g

|

0.48mg/9g |

132g

|

Approximately 15 tbsp |

So a small sprinkling of seeds on a salad, for example will not be sufficient to meet zinc requirements, especially in pregnancy. Maternal zinc deficiency can lead to poor birth outcomes and comprise infant development. Decreased supply of zinc to the foetus may occur from low plasma zinc concentrations reducing the transport of placental zinc. Maternal and foetal deficiency may also contribute to intra-uterine and systematic infections, often associated with pre-term birth, as zinc is crucial for normal immune function23.

Omega 3 fatty acids

Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) are essential for foetal brain, nervous system and retinal development throughout pregnancy. Health benefits are derived from omega-3 fatty acids docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) which the body produces from essential fatty acid alpha-linolenic acid. However, omega-3 alpha-linolenic acid, (ALA) and omega-6 linoleic acid, cannot be produced in the body and are therefore required through diet7. Pregnant women should aim for dietary intakes of at least 200mg DHA per day7. Vegan sources of omega-3 (ALA) include flaxseeds (linseeds), hemp seeds, mustard seeds, green leafy vegetables, walnut oil, spirulina, grains and oils made from rapeseed (canola), linseed (flaxseeds) and hemp seeds. Vegans may consume DHA supplements derived from microalgae to ensure adequate amounts of fatty acids in the diet. They are absorbed well and have positive influences on blood levels of DHA and EPA through the retro-conversion process24.

High intake of omega-6 (linoleic acid) in vegan diets may affect the conversion rate of omega-3 (ALA) to DHA in the body. Therefore vegans should reduce their consumption of safflower, sunflower and corn oils to achieve an improved balance of PUFAs in body tissues which will increase the production of DHA. Fatty acid consumption during lactation also needs consideration: To increase the amount of DHA the baby produces in their body, it is important to ensure that vegan mothers increase their consumption of dietary linolenic acid. Vegan breast milk contains differing proportions of polyunsaturated fatty acids compared to breastmilk of non-vegan women and this can be reflected in the body tissues of infants. However, there is no evidence of detrimental effects on a child’s development and growth24.

Recommended supplements

Folate (Folic Acid)

A 400mcg supplement of folic acid should be taken prior to conception and until the 12th week of pregnancy. If not taken before conception it should be taken immediately after knowledge of pregnancy. This is to reduce risks of neural tube defects such as spina bifida25. Pregnant women are also encouraged to increase dietary intake of folate and good sources for vegans include green leafy vegetables; cabbage, spinach, broccoli, asparagus and lettuce15. Some breakfast cereals are fortified with folic acid to increase dietary intake, however these sources may be unreliable during pregnancy as they do not contain sufficient levels25. Folate absorption is inhibited by prolonged cooking; it is a water soluble vitamin and is therefore susceptible to destruction, reducing the folate content in dietary sources. Therefore, all pregnant woman are recommended to take the synthetic form, folic acid in a tablet supplement15.

Vitamin D

All pregnant women are now recommended to take a supplement of 10mcg/day26. Vitamin D is essential for development of the foetal skeleton, steady growth throughout pregnancy and formation of tooth enamel, calcium absorption, cell differentiation, muscle function and bone health27. The mother’s vitamin D status is essential as the baby’s vitamin D status directly reflects the mother’s after birth. Maternal deficiency can result in pre-eclampsia, low birth weight, preterm labour, caesarean delivery and gestational diabetes7. Foods derived from animals generally have the highest vitamin D content; oily fish, meat and eggs. Therefore, vegans will have a greater risk of vitamin D deficiency7. Vitamin D2 fortified foods should be included such as breakfast cereals, spreads and some plant milks28. Deficiency in the UK is exacerbated by the lack of sunlight, limiting the action of vitamin D production in the skin and subsequent absorption by the body. Pregnant woman of African, African-Caribbean or South Asian origin, or women whose skin is mostly covered, will be at particular risk of developing deficiencies29.

Healthy Start Vitamins

The UK Department of Health recommends taking supplements containing specific nutrients during pregnancy. Women in receipt of certain benefits, or those under 18 years of age can apply for ‘Healthy Start’ Vouchers and Vitamins via a registered health professional from 10 weeks gestation and until the child is 4. The vitamins are important for lower income families due to reported reduced vitamin C intake and increased risk of vitamin D deficiency. Healthy start capsules contains 400mcg folic acid, 70mg vitamin C and 10mg vitamin D, and they are vegan friendly30.

How can vegan women ensure their intake of these ‘at risk’ nutrients?

Cereals and cereal products are often fortified with some at-risk nutrients helping vegans improve their dietary intake of micronutrients. In the UK, white and most brown flours must be fortified by law31 containing at least 1.65mg iron, 1.60mg niacin, and 0.24mg thiamin per 100g. Calcium carbonate is added to most flours equivalent to 94-156mg calcium to 100g flour, except wholemeal flour and some self-raising flours11. The range of nutrients added to breakfast cereals varies by brand and over time but can be a very useful source of vegan micronutrients.

Soya products are often fortified with calcium to provide similar quantities to cow’s milk; this can increase vegan consumption and plant milks are becoming increasingly popular32 (figure 4). However, non-soya milk alternatives, such as almond milk, although fortified with calcium can be deficient in other important nutrients such as protein (only providing 0.5g per 100ml) 33.

Figure 4: Table demonstrating the calcium content of cow’s milk compared to fortified soya milk.

|

Food Source |

Calcium Content Per Litre |

Calcium Content Per Litre After Fortification of Calcium |

|

Cow’s Milk |

1200mg |

N/A |

|

Soya Milk |

200mg |

+1000mg = 1200mg |

Restricted diets

The Zen macrobiotic diet is an extreme trend towards natural and organic foods, reducing animal products, consuming meals in moderation and consuming in-season, organic foods grown locally34. The fruitarian diet abstains from many food groups, consuming only fruit, vegetables; peppers and cucumber, nuts and grains. These overly restricted diets are not recommended during pregnancy as they lacks essential nutrients for a healthy pregnancy35. The raw food diet has similar exclusions as veganism, but also excludes food cooked over temperatures of 48˚C, focusing on fruits, nuts, seeds, sprouted grains and beans. It is not recommended during pregnancy and referrals to social services may be considered for women who ignore this advice36.

Conclusion

Vegan diets are increasing in popularity, especially with campaigns such as ‘Veganuary’; encouraging people to try a vegan lifestyle for the month of January37. Pregnant women may not be aware that their nutritional intake is at risk; believing their choice of diet to be beneficial to health. As a result, vegan women may not necessarily seek out professional health and support regarding diet before or during pregnancy. Vegan women can obtain their recommended nutritional intake during pregnancy, with careful monitoring of their diet. Unless a conscious effort to include plant sources of ‘at risk’ nutrients, frequently and in sufficient quantities, then vegan women are at risk of several micronutrient deficiencies during pregnancy. Micronutrient deficiencies can have a detrimental effect on maternal and foetal health and can result in poor pregnancy outcomes, including serious developmental restrictions or even foetal death. Several key nutrients may need to be added to the diet via supplements if dietary intakes are insufficient to avoid deficiency, primarily iron, zinc, iodine, vitamin B12 and omega-3 fatty acids38. Furthermore, there is a clear role for increased fortification of food targeting the vegan market, especially during pregnancy.

References

1 The Vegan Society (2017) Key Facts [online] Available at: https://www.vegansociety.com/about- us/key-facts [accessed: 29/01/17]

2 The Vegan Society (2017) Vegan babies and children – A dietary guide, including pre-conception and pregnancy [online] Available at: https://www.vegansociety.com/sites/default/files/Dietary_Guide_Vegan_Babies%2BChildren.pdf [accessed: 29/01/17]

3 The Vegan Society (2017) Raising Vegans – Research strongly supports vegan nutrition for babies and children [online] Available at: https://www.vegansociety.com/try-eco-magazine/raising-vegans [accessed: 29/01/17]

4 Lean, M.E.J. (2006) FOX AND CAMERON’S Food Science, Nutrition & Health 7th edition, United States of America: CRC Press

5 The Vegan Society (2017) The Overview – How to thrive on a plant-based diet [online] Available at: https://www.vegansociety.com/resources/nutrition-and-health/vitamins-minerals-and-nutrients/overview [accessed: 03/02/17]

6 Appleby, P.N., Key, T.J. & Rosell, M.S. (2006) Health effects of vegetarian and vegan diets Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 65:35-41

7 Derbyshire, E. (2014) Vegetarian and Vegan Pregnancy. In: Davies, L. & Deery, R. (eds) Nutrition In Pregnancy And Childbirth Food For Thought. New York: Routledge pp.86-97

8 COMA (1991) Dietary Reference Values for Food Energy and Nutrients for the United Kingdom 25th edition Report on Health and Social Subjects 41. London: TSO

9 Cassidy, A. Gibney, M.J., Lanham-New S.A. & Vorster, H.H. (2009) Introduction to Human Nutrition Second edition United Kingdom: The Nutrition Society

10 The Vegan Society (2017) Iron [online] Available at: https://www.vegansociety.com/resources/nutrition-and-health/vitamins-minerals-and-nutrients/iron [accessed: 03/02/17]

11 Berry, R., Church, S.M., Dodhia, S.K., Farron-Wilson, M., Finglas, P.M., Pinchen, H.M., Roe, M.A. & Swan, G. (2015) McCance and Widdowson’s The Composition of Foods. Seventh summary edition. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry

12 The Vegan Society (2017) Calcium [online] Available at: https://www.vegansociety.com/resources/nutrition-and-health/vitamins-minerals-and-nutrients/calcium [accessed: 03/02/17]

13 Ajaja, M., Jacquemyn, Y., Karepouan, N. & Van Sande, H. (2013) Vitamin B12 in pregnancy: Maternal and foetal/neonatal effects – A review, Open Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 3:599-602

14 The Vegan Society (2017) Vitamin B 12: your key facts [online] Available at: https://www.vegansociety.com/resources/nutrition-and-health/vitamins-minerals-and-nutrients/vitamin-b12-your-key-facts [accessed: 07/02/17]

15 Martin, C.R., Mullen, A. & Wratten, J. (2014) Micronutrients in pregnancy and lactation, In: Davies, L. & Deery, R. (eds.) Nutrition In Pregnancy and Childbirth Food For Thought. New York: Routledge pp.86-97

16 Paul, L. & Selhun, J. (2011) ‘Folic acid fortification: why not vitamin B12 also?’ Biofactors 37(4): 269-271

17 The Vegan Society (2017) Iodine [online] Available at: https://www.vegansociety.com/resources/nutrition-and-health/vitamins-minerals-and-nutrients/iodine [accessed: 06/02/17]

18 BDA (2016) Iodine [online] Available at: https://www.bda.uk.com/foodfacts/Iodine.pdf [accessed: 06/02/17]

19 Braverman, L.E., Lamar, A., Leung, A.M. & Pearce, E.N. (2011) ‘Iodine status and thyroid function of Boston-area vegetarians and vegans’ Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 96(8): 1303-1307

20 Kapil, U. (2007) Health Consequences of Iodine Deficiency, Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal 7(3): 267-272

21 The Vegan Society (2017) Zinc [online] Available at: https://www.vegansociety.com/resources/nutrition-health/vitamins-minerals-and-nutrients/zinc [accessed: 07/02/17]

22 Moran, V.H. (2014) Nutritional Needs For Lactation. In: Davies, L. & Deery, R. (eds.) Nutrition In Pregnancy and Childbirth Food For Thought. New York: Routledge pp. 35-55

23 Darton-Hill I. (2013) Zinc supplementation during pregnancy [online] Available at: http://www.who.int/elena/bbc/zinc_pregnancy/en/ [accessed: 14/02/17]

24 The Vegan Society (2016) Essential Fatty Acids [online] Available at: https://www.vegansociety.com/sites/default/files/Omega%203%20and%20Omega%206%20Essential%20Fatty%20Acids.pdf [accessed: 09/02/17]

25 NHS (2017) Vitamins, supplements and nutrition in pregnancy [online] Available at: http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/pregnancy-and-baby/pages/vitamins-minerals-supplements-pregnant.aspx [accessed: 15/02/17]

26 SACN (2016) Vitamin D and health. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/537616/SACN_Vitamin_D_and_Health_report.pdf [accessed 27/02/2017]

27 Dawoda, A., Hollis, B.W., Johnson, D.D., Taylor, S.N. & Wagner, C.L. (2012) Vitamin D and its role during pregnancy in attaining optimal health of mother and foetus. Nutrients 4(3): 208-230

28 The Vegan Society (2017) Team up for healthy bones [online] Available at: https://www.vegansociety.com/resources/nutrition-and-health/team-healthy-bones [accessed: 17/02/17]

29 NHS (2017) Vitamins and minerals – Vitamin D [online] Available at: http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/vitamins-minerals/Pages/Vitamin-D.aspx [accessed: 16/02/17]

30 Healthy Start (2017) Healthy Start Vitamins [online] Available at: https://www.healthystart.nhs.uk/healthy-start-vouchers/healthy-start-vitamins/ [accessed: 18/02/17]

31 The Bread and Flour Regulations (1998) Statutory Instrument No. 141. London: The Stationery Office

32 Soya (2014) Calcium Fortification of Soy Milk [online] Available at: http://www.soya.be/soy-milk-calcium.php [accessed: 19/02/17]

33 Alpro Almond Milk (2017) Available at https://www.alpro.com/uk/products/drinks/almond/original-fresh [accessed 27/02/17]

34 JAMA (1971) Zen Macrobiotic Diets JAMA 218(3):397

35 Boyle, J. (2011) Vegetarianism and fruitarianism as deviance In: Bryant, C.D. (ed.) The Routledge Handbook of Deviant Behaviour. New York: Routledge pp.266-268

36 Tuso, P.J. (2013) Nutritional Update for Physicians: Plant-Based Diets. The Permanent Journal 17(2): 61-66

37 Veganuary (2017) Veganuary [online] Available at: https://veganuary.com/ [accessed: 19/02/17]

38 Attini, R., Avagnina, P., Cabidda, G., Capizzi, I., Castelluccia, N., Clari, R., Colombi, N., Leone, F., Mauro, G., Pani, A., Piccoli, G.B., Todros, T. & Vigotti, F.N. (2015) Vegan-vegetarian diets in pregnancy danger or panacea? A systematic narrative review An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 122(5): 623-633

Check out New Food’s Health Ingredients month here:

Health Ingredients Month

Tom Clifford, PhD, Sport and Exercise Nutrition, University of Northumbria – Can beetroot help relieve muscle pain after exercise?

Petr Menšík, Manager, EU Affairs, ECCO, The European Consulting Company – Defining the term ‘natural’ in food and beverage

Claus Andersen, Category & Application Manager, Arla Foods Ingredients – How dairy can lead a new waste revolution

Alex Murtough, Field & Marketing Manager, Oppo – Healthy food? It’s out of reach for most of us

Kevin Bael, Product Manager, Specialty Rice Ingredients, Beneo – The unique, natural value of rice starch

Andrea Zangara, Centre for Human Psychopharmacology, Swinburne University – Plant-based ingredients and their cognitive benefits

Marc Fremont, Ph.D. R&D director, VF Bioscience SAS – Cell culture: an innovative approach for production of plant actives

Lindsey Bagley, BA, CSci, FIFST, Flavour Horizons – Lifting the lid on the clean label trend

Vitafoods 2017

To get in touch with a representative from New Food at Vitafoods 2017, click here.

no.

why not eat properly?

or is that too “unfashionable”?

Popeye was fake news. Unlike heme-bound iron in meat, the iron bio-availability in spinach is very low due to its phytate content which prevents it being absorbed from the gut.

says the dietitian with the doctorates… ha!

Well done and thank you; a really clear and useful update on this confusing and much-discussed subject

Thank you!

Really interesting! I don’t think people realise the importance a diet can have on the development of a child – both during pregnancy and future development.

A lot of good points in this article – Great read!

This is really insightful. Thrilling read!